Higher Wages and Affordable Housing: Top Needs for New Yorkers to Get Ahead Economically

Irene LewEmerita TorresDebipriya Chatterjee

Context

While New York City’s pandemic-ravaged economy is gradually rebounding by some metrics, it has a long way to go towards an inclusive recovery that benefits all New Yorkers. When he takes office in January 2022, New York City Mayor-Elect Eric Adams will inherit a $5 billion budget deficit[1] and an acute housing and homelessness crisis exacerbated by widespread pandemic-related job loss. As the city looks ahead to the next mayoral administration, it must center the needs of low-income New Yorkers, especially communities of color, who continue to struggle. For nearly 20 years, the Unheard Third survey has tracked the hardships of New York City's low-income residents and their views on what policies would help them get ahead, making it the longest-running regular public opinion poll of low-income households in the United States. This post is the first in a special series, Whose Recovery? Addressing the Needs of Low-Income New Yorkers, which highlight key findings from our 2021 Unheard Third on the lingering and inequitable impacts of COVID-19.

Key Findings

-

Across incomes, the top two (of ten) measures selected by low-income New Yorkers to help them get ahead are higher wages and affordable housing.

-

Nearly 6 in every 10 low-income essential workers chose higher wages as a top priority for helping them get ahead economically, by a much wider margin than low-income New Yorkers overall.

-

Affordable housing was the top priority among low-income Black New Yorkers, while higher wages ranked at the top of the list for low-income Latina/o/x and Asian residents.

-

Compared to all low-income respondents, working mothers were twice as likely to rank childcare affordability as a top measure for getting ahead.

Summary of Recommendations

-

Housing affordability: Enact the Housing Access Voucher Program; support conversions of for-profit real estate into social housing models; ending the tax lien sale; support Community Land Trusts; and pass the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act and Community Opportunity to Purchase Act.

-

Housing coordination: Bring disparate planning and budgeting processes together to establish a comprehensive, integrated housing plan that combines affordable housing, homelessness, and public housing.

-

Public Housing: Improve conditions in public housing and close NYCHA’s ongoing budget gaps.

-

Wages: Invest federal funding for local recovery efforts in expansion of job training; End the subminimum wage for all tipped workers in New York State by passing One Fair Wage legislation.

-

Workforce development coordination: Appoint and empower a senior city administration official to improve coordination of the city’s workforce development system and strategy, and fully integrate city’s workforce development systems and policies into the city’s overall economic development strategy.

Introduction

Nearly two years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, 80 percent[2] of adult New York City residents are fully vaccinated against COVID-19, sales tax revenue has rebounded[3], and the citywide unemployment rate of 9.4 percent[4] is a notable decline from the May 2020 peak of 20 percent. By some metrics, the city’s pandemic-ravaged economy is gradually rebounding, but it has a long way to go towards a full and inclusive recovery that benefits all New Yorkers. The pandemic exposed—and worsened—racial inequities in access to healthcare, jobs, housing, and beyond. The unemployment rates among Black (12 percent) and Latina/o/x New Yorkers (11 percent) remain well above the rates for White (7.5 percent) and Asian (7.3 percent) residents. Furthermore, tenants in predominantly Black and Latina/o/x neighborhoods hit hardest by COVID-19 continue to face high levels of housing insecurity and remain at greater risk of being evicted from their homes when the state eviction moratorium expires in January 2022.

As the city looks ahead to the next mayoral administration, it must center the needs of low-income New Yorkers, overwhelmingly people of color, who continue to experience significant hardship and struggle to get ahead. This post is the first in a special series, Whose Recovery? Addressing the Needs of Low-Income New Yorkers, which will highlight key findings from our 2021 Unheard Third on the lingering inequitable impacts of COVID-19. For nearly 20 years, the Unheard Third has tracked the hardships of New York City's low-income residents and their views on what policies would help them get ahead, making it the longest-running regular public opinion poll of low-income households in the United States. Topics for this series will include the challenges low-income New Yorkers face in the job market; struggles with achieving housing stability; transit affordability; the hardships of the app-based gig workforce; the disproportionate impact of student debt burdens; the digital divide, and more. The survey also sought out respondents’ views on measures that would strengthen the economic security of low-income New Yorkers, including the awareness of important programs like Fair Fares and of labor standards like paid sick leave.

This introductory brief covers how New Yorkers responded to a question we posed in the 2021 Unheard Third on what it would take to help low-income New Yorkers get ahead:

Q: Low-income respondents: Which two of the following would most increase your potential to get ahead economically? (Rank top two choices)

Q: Moderate-higher income respondents: Which two of the following would most increase low-income people’s potential to get ahead economically? (Rank top two choices)

Choices:

-

Increased access to job training

-

More affordable college

-

Stronger enforcement of workplace protections

-

Access to affordable healthcare

-

More pathways to citizenship for immigrants

-

Affordable childcare

-

Public investment in infrastructure to create jobs

-

Affordable housing

-

Higher wages

-

Fewer government regulations on businesses

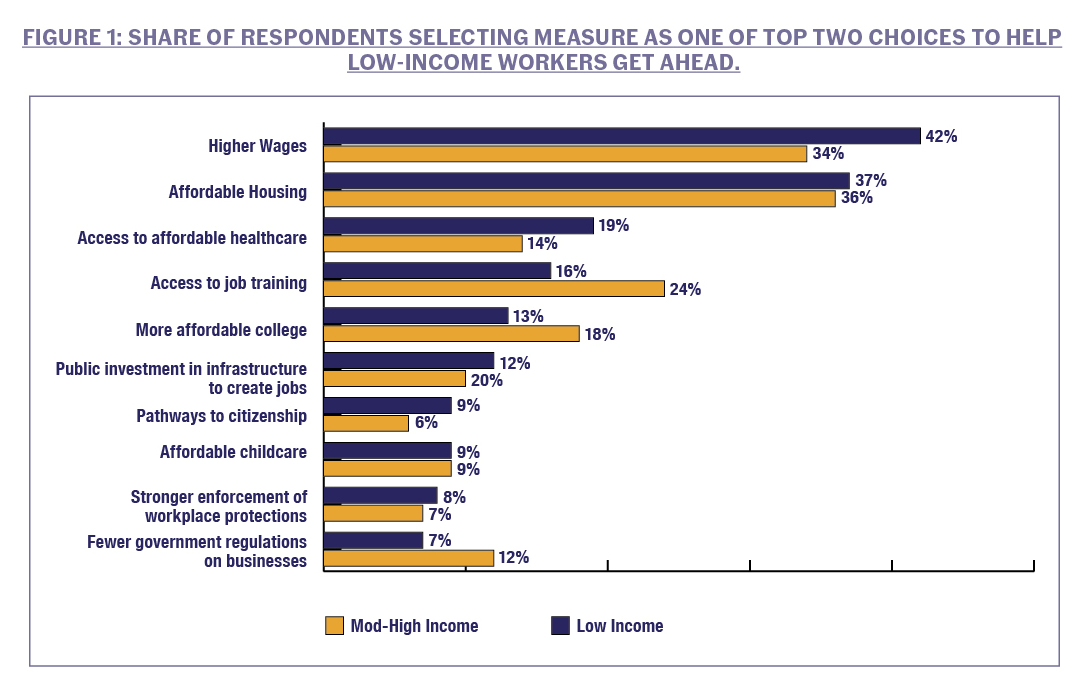

Across incomes, the top two measures selected to help low-income New Yorkers get ahead were higher wages and affordable housing.

From a list of 10 measures that were presented, low-income New Yorkers overwhelmingly selected higher wages and affordable housing as measures they believe would help them get ahead economically. Figure 1 shows that 42 percent of low-income New Yorkers selected higher wages as one of their top two choices, followed by 37 percent choosing affordable housing. Access to affordable healthcare was a distant third with 19 percent citing it as one of the top two concerns.

Among moderate- to higher- income New Yorkers, affordable housing slightly edged out higher wages as having the most potential for helping low-income New Yorkers get ahead. There was also more support among moderate- to higher- income respondents for increased access to job training (24 percent) and public investment in infrastructure to create jobs (20 percent).

Below we analyze the responses to this question on economic mobility for various demographic and socio-economic subgroups.

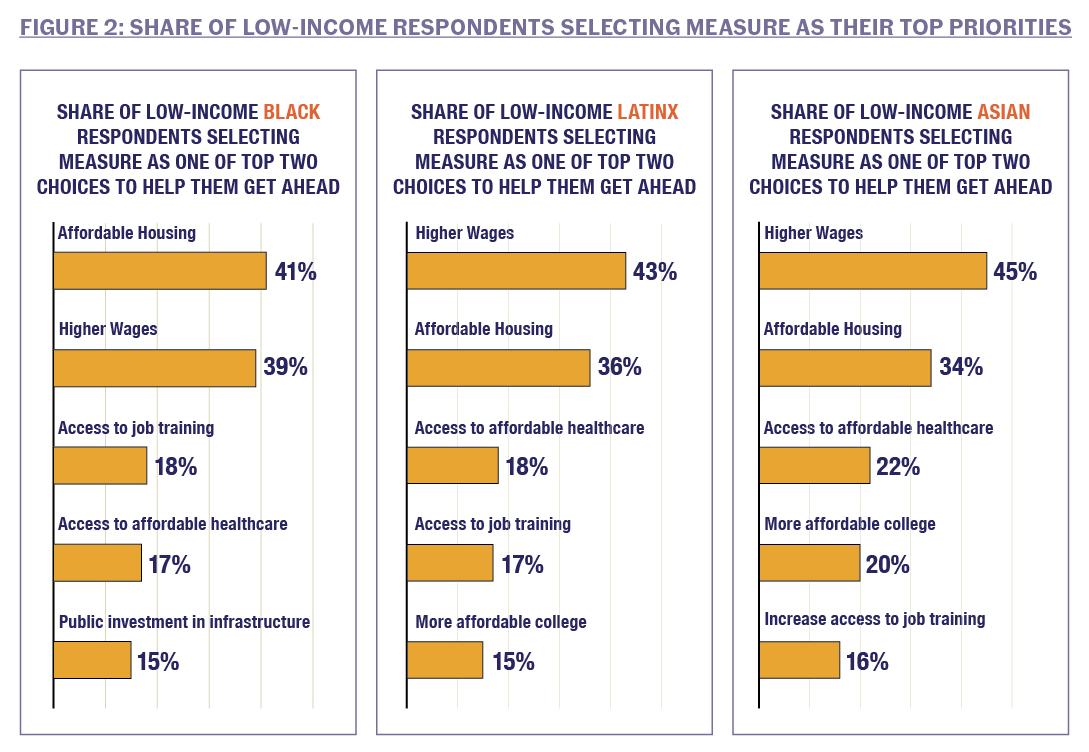

Affordable housing was the top priority among low-income Black New Yorkers, while higher wages ranked at the top of the list for low-income Latinx and Asian respondents.

Figure 2, across three panels, shows the responses of low-income New Yorkers by race and ethnicity. Low-income New Yorkers, across race and ethnicity, ranked affordable housing and higher wages as their top two measures. Yet there was a slight divergence at the top of the list: higher wages was the most popular measure among low-income Latina/o/x and Asian respondents, but low-income Black respondents ranked affordable housing as their top measure for getting ahead. Meanwhile, low-income Asian New Yorkers were more likely to select more affordable college as a means to helping them get ahead: one in five low-income Asian residents (20 percent) selected college affordability as one of their top two measures, compared to 15 percent of low-income Latina/o/x and 11 percent of Black residents.

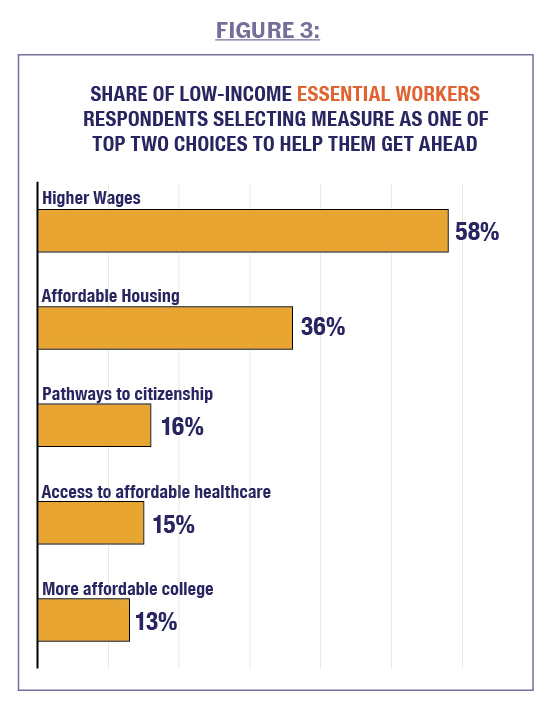

Nearly 6 in every 10 low-income essential workers chose higher wages as a top priority for helping them get ahead economically.

Figure 3 shows that 58 percent of low-income essential workers[5] we surveyed ranked higher wages as a top priority for getting ahead, well above the 42 percent of all low-income respondents who selected this as a top measure. Furthermore, 16 percent of low-income essential workers selected pathways to citizenship by a much larger margin than all low-income respondents (9 percent). Throughout the pandemic, essential workers, such as those working in healthcare, restaurants and food delivery kept the city running by keeping New Yorkers safe, fed and healthy. Furthermore, recent research has found that essential workers make up the vast majority of New York State’s undocumented labor force.[6] Yet, essential workers have not been appropriately compensated for the additional risk of COVID-19 exposure that they face on the job, and most have been excluded from COVID-19 related assistance programs.

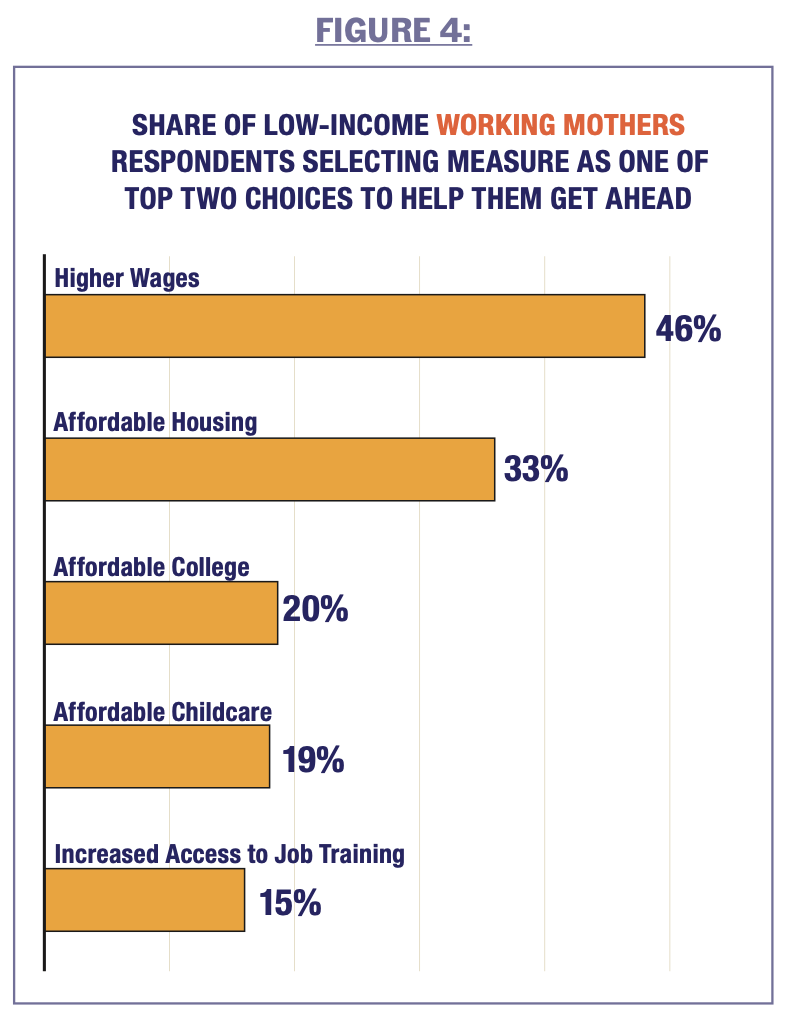

Compared to all low-income respondents, working mothers were twice as likely to rank childcare affordability as a top measure for getting ahead.

Figure 4 shows that low-income working mothers overwhelmingly selected higher wages and affordable housing as their top two measures for getting ahead. Nearly half of low-income working mothers listed higher wages as one of their top priorities for economic mobility, and more than a third selected affordable housing. But low-income working mothers were twice as likely as low-income respondents overall to select affordable childcare as a top priority for helping them get ahead (18 percent of low-income working mothers compared to 9 percent of all low-income respondents). This is reflective of the challenging transition to remote schooling and the difficulties that many mothers faced with access to affordable child care during the pandemic. Low-income mothers were also more likely than low-income respondents overall to select more affordable college as a priority for getting ahead (18 percent vs. 13 percent of all low-income respondents), suggesting affordable higher education as a growing concern.

Conclusion and recommendations

Mayor-elect Eric Adams needs to be ready on day one with a comprehensive slate of solutions aimed at housing, education, and workforce development, to ensure that New York City’s low-income residents have full access to economic opportunity.

Housing affordability

Nearly half of low-income respondents identified housing affordability as a challenge in 2021. Low-income New Yorkers have long struggled to pay the rent. Temporary pandemic measures, like the state eviction moratorium, provided some reprieve. However, with the moratorium set to expire and Governor Kathy Hochul’s recent announcement that the state’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) has run out of funding and would stop taking applications in most parts of the state, hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers are at risk of homelessness. Although Governor Hochul has requested nearly $1 billion in additional funding for ERAP from the federal government, a back-up plan is necessary should this request be denied. Measures must be taken at both the city and state level to ensure that low-income New Yorkers can remain stably housed, while boosting the city’s affordable housing supply. Below are critical recommendations to address housing affordability in New York.

To ensure a more effective, coordinated response to the housing crisis, the next mayoral administration should have one deputy Mayor responsible for all housing matters, including affordable housing, addressing homelessness, and public housing.

1. Establish an integrated, comprehensive city housing plan

To ensure a coordinated, effective response to the persistent housing affordability crisis, the city should bring disparate planning and budgeting processes together to establish a comprehensive housing plan that combines affordable housing, homelessness, and public housing.

2. Enact a Statewide Housing Access Voucher Program

New York State should enact the Housing Access Voucher Program, a widely available and easy to use tool to make housing affordable to homeless and low-income New Yorkers. Proposed by Senator Brian Kavanaugh, the program would provide emergency rental assistance to individuals and families in homeless shelters and those at risk for becoming homeless due to COVID-19-related loss of income.

3. Support city and state conversions of for-profit real estate into social housing

New York City and State should support conversions of for-profit real estate into social housing models by expanding the funding and scope of the Housing Our Neighbors with Dignity Act (HONDA), ending the tax lien sale, supporting Community Land Trusts, and passing the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act and Community Opportunity to Purchase Act.

4. Improve and invest in public housing

Government at all levels must act to improve conditions in public housing and close NYCHA’s ongoing capital and operating budget gaps. This includes both committing capital and revising rules to enable the housing authority to put those funds to fast and good use.

Higher Wages

That low-income workers overwhelmingly chose ‘higher wages’ as the most important factor for economic mobility is not surprising. For decades, several policy choices have enabled wage suppression by allowing employers to systematically dismantle unions, outsource and offshore jobs, impose non-compete clauses in contracts, and re-classify workers as independent contractors.[7] Even as workers’ productivity continued to increase, their compensation did not, as most of the profits from increased productivity was captured by employers.[8] The consequences of stagnant wages is perhaps higher for workers in New York City—the most unequal city in the nation—as they struggle to afford living in an increasingly expensive city.[9] Addressing the absence of wage growth will require engagement of all stakeholders and a multi-pronged action plan. We list key actionable recommendations below the city and state policymakers to consider.

1. Invest federal funding for local job training expansion

The American Rescue Plan signed into law in March 2021 set aside $360 billion in funding for state and local COVID-19 recovery efforts, with New York City receiving an estimated $4 million in direct aid.[10] Part of this funding can be used to support job training efforts across the workforce continuum, starting in the K-12 education system, to create a pipeline to higher-paying jobs. This includes investment in work-based learning opportunities in public schools, bridge programs to postsecondary education and training opportunities, sector-based skills training and apprenticeships.[11]

2. End the subminimum wage for tipped workers in NY

We must ensure that all workers in New York state—regardless of whether they receive tips or not—are guaranteed the minimum wage. When former Governor Andrew Cuomo eliminated the subminimum wage for tipped workers in industries like car washes and nail salons, he left behind restaurant workers. The state legislature should pass A2244/S808, sponsored by Senator Alessandra Biaggi and Assemblymember Catalina Cruz, to end the subminimum wage for all tipped workers in New York State.

3. Create a coordinated workforce development system that delivers good paying jobs

To ensure that more New Yorkers can access the job training, education and employment services they need to get ahead, the next Mayor should appoint and fully empower a senior administration official that would be held accountable for coordinating the city’s workforce development system and strategy, including establishing citywide goals for economic recovery and evaluating success using common metrics.[12] The city’s workforce development systems and policies should be fully integrated into the city’s overall economic development strategy—this would help ensure that economic and business development proposals received by the NYC Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) provide meaningful, high-paying training and job opportunities to New Yorkers who have historically been excluded from good-paying sectors like tech.[13]

Survey Methodology

The Community Service Society of New York designed this survey in collaboration with Lake Research Partners, who administered the survey by phone using professional interviewers. The survey was conducted from July 8th through August 10th, 2021. The survey reached a total of 1,763 New York City residents, age 18 or older, divided into two samples. 1,110 low-income residents (up to 200% of federal poverty standards, or FPL) comprise the first sample including 533 poor respondents, from households earning at or below 100% FPL (69.4% conducted by cell phone) and 577 near-poor respondents, from HH earning 101% - 200% FPL (71.1% conducted by cell phone). 653 moderate- and higher-income residents (above 200% FPL) comprise the second sample, including 389 moderate-income respondents, from HHearning 201% - 400% FPL (70.2% conducted by cell phone) and 264 higher-income respondents, from HH earning above 400% FPL (61.7% conducted by cell phone).

Landline telephone numbers for the low-income sample were drawn using random digit dial (RDD)among exchanges in census tracts with an average annual income of no more than $44,660. Telephonenumbers for the higher-income sample were drawn using RDD in exchanges in the remaining censustracts. The data were weighted slightly by income level, gender, region, age, immigrant status, and racein order to ensure that it accurately reflects the demographic configuration of these populations.Interviews were conducted in English (1,662), Spanish (83), and Chinese (18). The low-income samplewas weighted down into the total to make an effective sample of 600 New Yorkers.

In interpreting survey results, all sample surveys are subject to possible sampling error; that is, theresults of a survey may differ from those which would be obtained if the entire population wereinterviewed. The size of the sampling error depends on both the total number of respondents in thesurvey and the percentage distribution of responses to a particular question. The margin of error for theentire survey is +/- 2.3%, for the low-income component is +/- 2.9%, and for the higher-incomecomponent is +/- 3.8%, all at the 95% confidence interval.

For questions related to the survey, please reach out to Emerita Torres, Vice President of Policy Research and Advocacy, at etorres@cssny.org.

Footnotes

1. Hicks, Nolan and Bruce Golding. New York Post. “NYC’s next mayor faces $5.4B budget deficit after de Blasio adds another $300M.” https://nypost.com/2021/07/13/nycs-next-mayor-faces-5-4b-budget-deficit-after-de-blasio-quietly-adds-300m/. July 13, 2021.

2. NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: COVID-19 Vaccine data. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data-vaccines.page#people

3. Office of the NYS Comptroller. “DiNapoli: Statewide Local Sales Tax Collections Surge Nearly 58 Percent in May.” https://www.osc.state.ny.us/press/releases/2021/06/dinapoli-statewide-local-sales-tax-collections-surge-nearly-58-percent-may. June 16, 2021.

4. As of October 2021, from the NYS Department of Labor (https://dol.ny.gov/labor-statistics-new-york-city-region)

5. In our Unheard Third survey data, we identified essential workers as an employed respondent working in one of the following industries identified by the NYS executive order (https://esd.ny.gov/guidance-executive-order-2026) as an essential industry—healthcare, restaurants, food service, food delivery, transportation, construction or hotels—and also reported that they did not work from home at all.

6. Center for Migration Studies of New York. “Immigrants Comprise 31 Percent of Workers in New York State Essential Businesses and 70 Percent of the State’s Undocumented Labor Force Works in Essential Businesses.” https://cmsny.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Printable-New-York-Essential-Workers-Report.pdf. May 2020.

7. Mishel, Lawrence and Josh Bivens. “Identifying the policy levers generating wage suppression and wage inequality”, Economic Policy Institute, Unequal Power, May 13, 2021.

8. Mishel, Lawrence. “Growing inequalities, reflecting growing employer power, have generated a productivity–pay gap since 1979”, Economic Policy Institute, Working Economics Blog, September 2, 2021.

9. Parrott, James. “Low-wage workers and the high cost of living in New York City.” Testimony presented to New York City Council Committee on Civil Service and Labor, 2014. http://www.fiscalpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/FPI-Parrott-testimony-Low-Wage-workers-and-Cost-of-iving-Feb-27-2014.pdf

10. Office of Sen. Chuck Schumer. “The American Rescue Plan: New York State and Local aid Breakdown.” https://www.schumer.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/ARPNYLocal%20Aid31221.pdf. March 2021.

11. Invest in Skills NY. “Recommendations for an Equitable Economic and Workforce Recovery Prioritizing People, Community and Systems.” https://www.investinskillsny.org/invest-in-skills-ny-nyc-campaign

12. Invest in Skills NY. “Recommendations for an Equitable Economic and Workforce Recovery Prioritizing People, Community and Systems.” https://www.investinskillsny.org/invest-in-skills-ny-nyc-campaign. September 2021.

13. NYC Inclusive Growth Initiative. “Inclusive Growth Blueprint. A Model for Equitable Development in New York City.” https://nycetc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/New-York-City-Inclusive-Growth-Initiative-Inclusive-Growth-Blueprint.pdf. August 2021.