Testimony: Why New York Needs Universal Rent Control

Oksana Mironova

NYS Assembly Standing Committee on Housing

Rental Housing & Tenant Protections

Testimony by Oksana Mironova, CSS Housing Policy Analyst

May 9, 2019

Thank you for this opportunity to comment on the issue of rent stabilization and tenant protections in New York State. My name is Oksana Mironova and I am a Housing Policy Analyst at The Community Service Society (CSS), an independent nonprofit organization that addresses some of the most urgent problems facing low-income New Yorkers and their communities, including the effects of the city’s housing affordability crisis.

New York City is rapidly losing its low-rent apartments, creating a housing market where low-income tenants are squeezed between a rock and a hard place: severe rent burdens at home and no easily accessible alternatives on the market. Other high renter cities like Rochester, Syracuse, Albany, and Troy are seeing the emergence of a similar dynamic, leading to evictions, doubling up, and homelessness for many.

To address this statewide crisis, the Community Service Society endorses the Universal Rent Control platform of the Upstate Downstate Housing Alliance, which will both close destructive loopholes within the rent stabilization laws and enable communities across New York State to opt into a system that moderates rent increases and protects tenants from unjust evictions. We also strongly support the Home Stability Support proposal for expanded rent assistance subsidies for families receiving public assistance and the rest of the alliance’s End Homelessness platform.

In our research, we have found that tenants are losing ground in New York City, while landlords are continuing to profit:

- The typical rent stabilized household was earning the same inflation adjusted amount in 2016 as in 2001, while typical rents climbed by 30 percent above inflation (see figures 1 and 2).

- Among low-income stabilized tenants, the median rent to income ratio–the share of income a household spends on rent–increased from 40 percent in 2002 to 52 percent in 2017 (see figure 3).

- With high-rent burdens and limited choice within the market–low-rent apartment vacancy was about 2 percent in 2017–many low-income New Yorkers find themselves in extremely difficult housing situations. Among low-income stabilized renters, nearly half reported being unable to afford a $25 increase in rent in 2018 (see figure 4).

- At the same time, according to the latest Rent Guidelines Board (RGB) data, landlords of stabilized buildings spent about 59 cents out of every revenue dollar on operations, thus generating 41 cents in income.

- Outcomes for stabilized tenants, particularly those who are low-income, are getting worse. The major culprits for this are the vacancy bonus, Major Capital Improvements (MCI), Individual Apartment Improvements (IAIs), preferential rents, and vacancy decontrol. While they may seem like reasonable provisions for ensuring the maintenance of the city’s housing stock, these loopholes all work in tandem to push out low-income tenants and undermine neighborhood-level stability because they erode the effectiveness of the rent stabilization system (see figures 5 and 6).

- Low-rent apartments are disappearing both because of the destructive impact of rent law loopholes on rental submarkets in the Bronx, upper Manhattan, and central Brooklyn, as well as the loss of unregulated low-rent units in low-density neighborhoods of Queens, Staten Island, and outer Brooklyn. City-wide, the share of unassisted low-rent apartments (approximately $900 in 2011 and $990 in 2017) fell from 21 percent to 14 percent between 2011 and 2017, from 445,000 to 300,000 units (see figure 8).i

The Emergency Tenant Protection Act (ETPA) is a powerful tool that protects about a million renter households in New York State. However, over the past 25 years, legislative decisions by the city and state have weakened rent regulation, encouraging tenant harassment and allowing for sudden and permanent rent hikes. The same loopholes create an environment where fraud is rampant. The vacancy bonus, Major Capital Improvements (MCI), Individual Apartment Improvements (IAIs), preferential rents, and vacancy decontrol all work in tandem to push out low-income tenants and undermine neighborhood-level stability. New York City has lost 291,000 stabilized units since 1994.

The housing crisis has an even greater impact on the state’s unregulated tenants both in New York City and the rest of the State. Areas not covered by the ETPA, The Hudson Valley, the Capital District, and Central New York, have all seen the rapid loss of low-rent units.

Local governments in all parts of the state should be eligible to opt in to rent stabilization, and tenants throughout the state should be protected from arbitrary eviction even where rents are not regulated. The tenants who would benefit from good cause eviction protections are most concentrated in high-renter cities that are not subject to rent stabilization. But, Assemblymember Hunter’s bill would also help almost 600,000 households in New York City that live either in deregulated apartments or in small buildings, as well as almost 180,000 households in Westchester, Rockland, and Nassau counties.

To close the rent law loopholes and expand renter protections, the Community Service Society endorses the Universal Rent Control platform of the Upstate Downstate Housing Alliance.

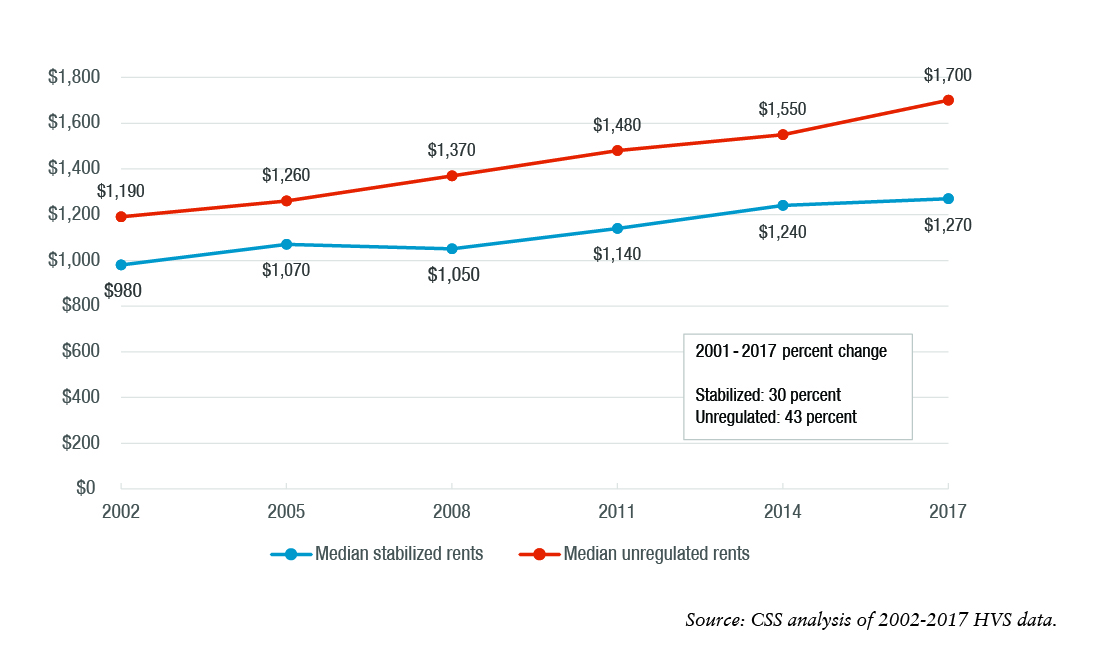

Figure 1: Median rents in stabilized and unregulated apartments since 2002 (2017 Dollars)

Among stabilized tenants in New York City, median rents have grown by 30 percent above inflation since 2002. It is important to note that tenant turnover in rent stabilized units influences this comparison. However, stabilized tenants are, overall, fairly stable: The average stabilized tenant has lived in their apartment for 14 years.

The main culprits for the rapid rise of stabilized rents are the rent law loopholes–vacancy deregulation, the vacancy bonus, Major Capital Improvements (MCI), Individual Apartment Improvements (IAIs), and preferential rents–which allow landlords to raise rents well above the annual guidelines. While these sound like reasonable provisions to incentivize landlords to invest in upgrading their units, in practice they have been rife with fraud and abuse leading to unwarranted rent increases and displacement.

Median unregulated rents also rose substantially since 2002, increasing by 43 percent above inflation. This widened the gap between the typical regulated and unregulated apartment to $430.

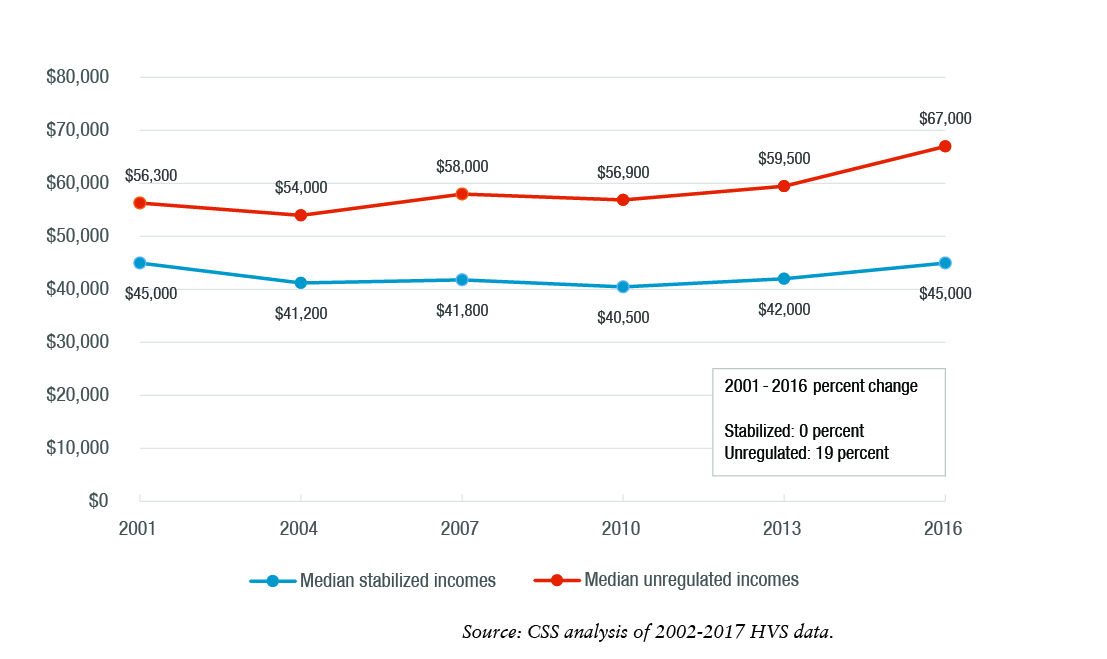

Figure 2: Median incomes in stabilized and unregulated apartments since 2001 (2016 Dollars)

Rents have far outpaced incomes in stabilized apartments. Even though median rents climbed by 30 percent above inflation, the typical stabilized household was earning the same inflation-adjusted amount in 2016 as in 2001.

For the better part of the 2000s, median incomes for tenants living in rent stabilized apartments were in a long period of stagnation, declining from $45,000 in 2001 to $40,500 in 2010 (in 2016 dollars). Incomes began rising in 2010, recovering to their inflation-adjusted 2001 level by 2016.ii

Inflation-adjusted median incomes for tenants living in unregulated apartments have been on an upward trajectory, even though they also experienced dips in 2004 and in 2008, as a result of the economic impact of 9/11 and the recession.

The income gap between regulated and unregulated units has doubled from $11,300 in 2001 to $22,000 in 2016, a result of new luxury development and vacancy deregulation (threshold currently set at $2,775) of stabilized apartments in Manhattan below 96th Street.

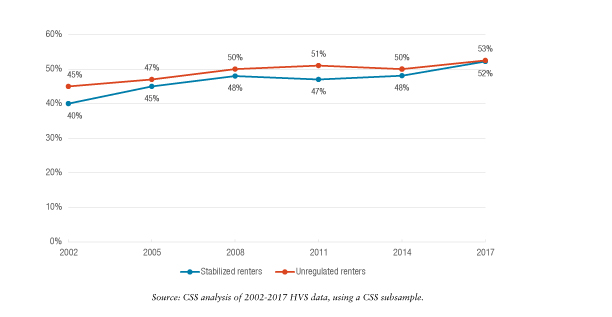

Figure 3: Median rent to income ratio among low-income New Yorkers since 2002iii

Rent stabilized tenants’ incomes have not kept up with rising rents. As a result, the median rent to income ratio –the share of income a household spends on rent –among low-income stabilized households increased from 40 percent in 2002 to 52 percent in 2017.

Typically, renters who spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent are considered rent burdened; those who spend 50 percent of their income on rent are considered severely rent burdened.

While rent stabilization is not a housing subsidy program, it has helped to indirectly lower rent burdens among low-income tenants in the past. By 2017, the gap between stabilized and unregulated low-income tenant rent burdens essentially disappeared.

Figure 4: Share of low-income tenants unable to afford a $25 increase in monthly rent (2018)

With high-rent burdens and limited choice within the market (low-rent apartment vacancy was about 2 percent in 2017),iv many low-income New Yorkers find themselves in extremely difficult housing situations. Among low-income stabilized renters, nearly half reported being unable to afford a $25 increase in rent in 2018.

According to homeless advocacy groups like Picture the Homeless and Coalition for the Homeless, as well as the city’s own research, the city’s homelessness crisis is directly tied to the growing housing affordability gap, driven in no small part by increasing rents. The number of people sleeping in a shelter each night rose from 31,000 in year 2002 to 64,000 in 2019.v

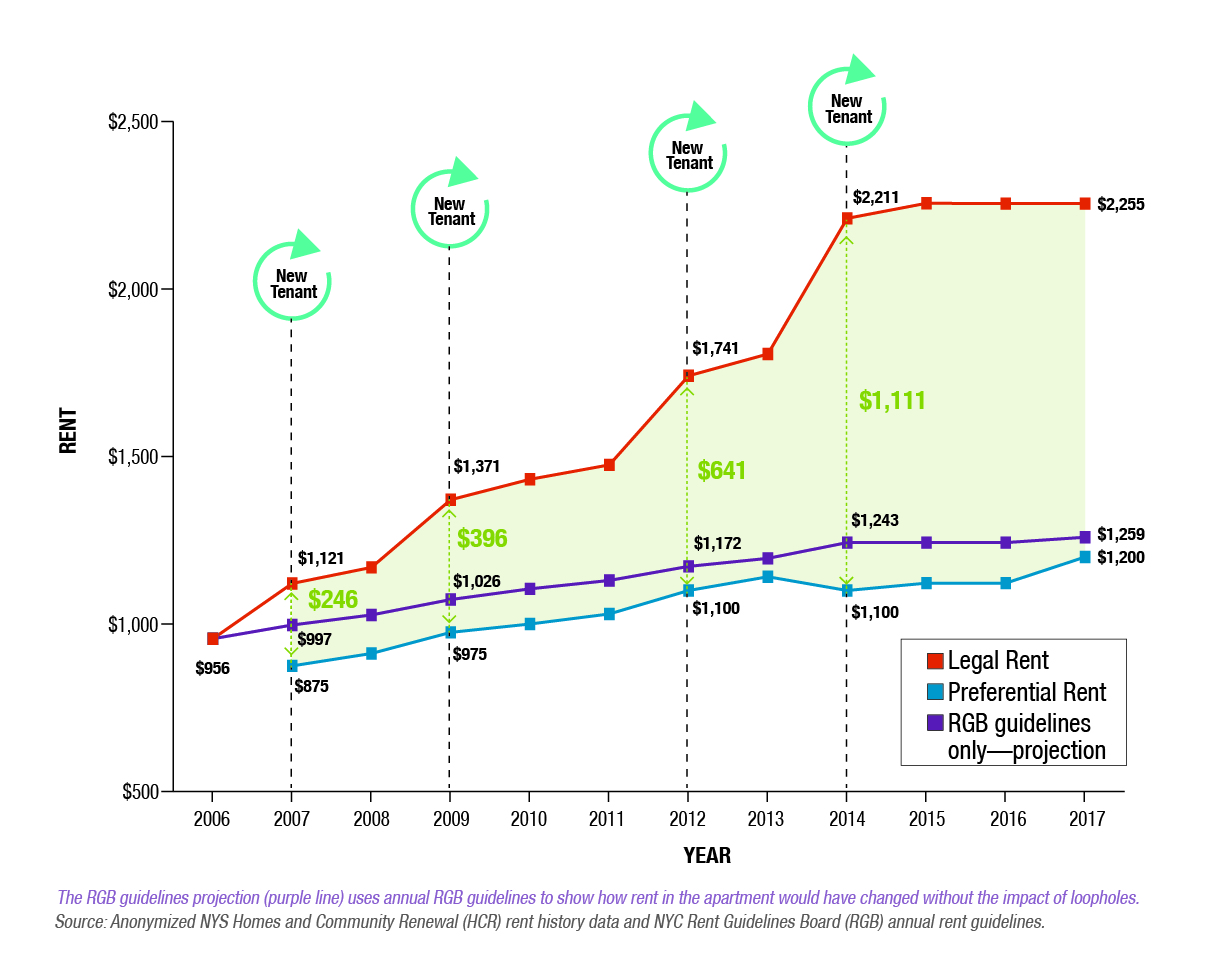

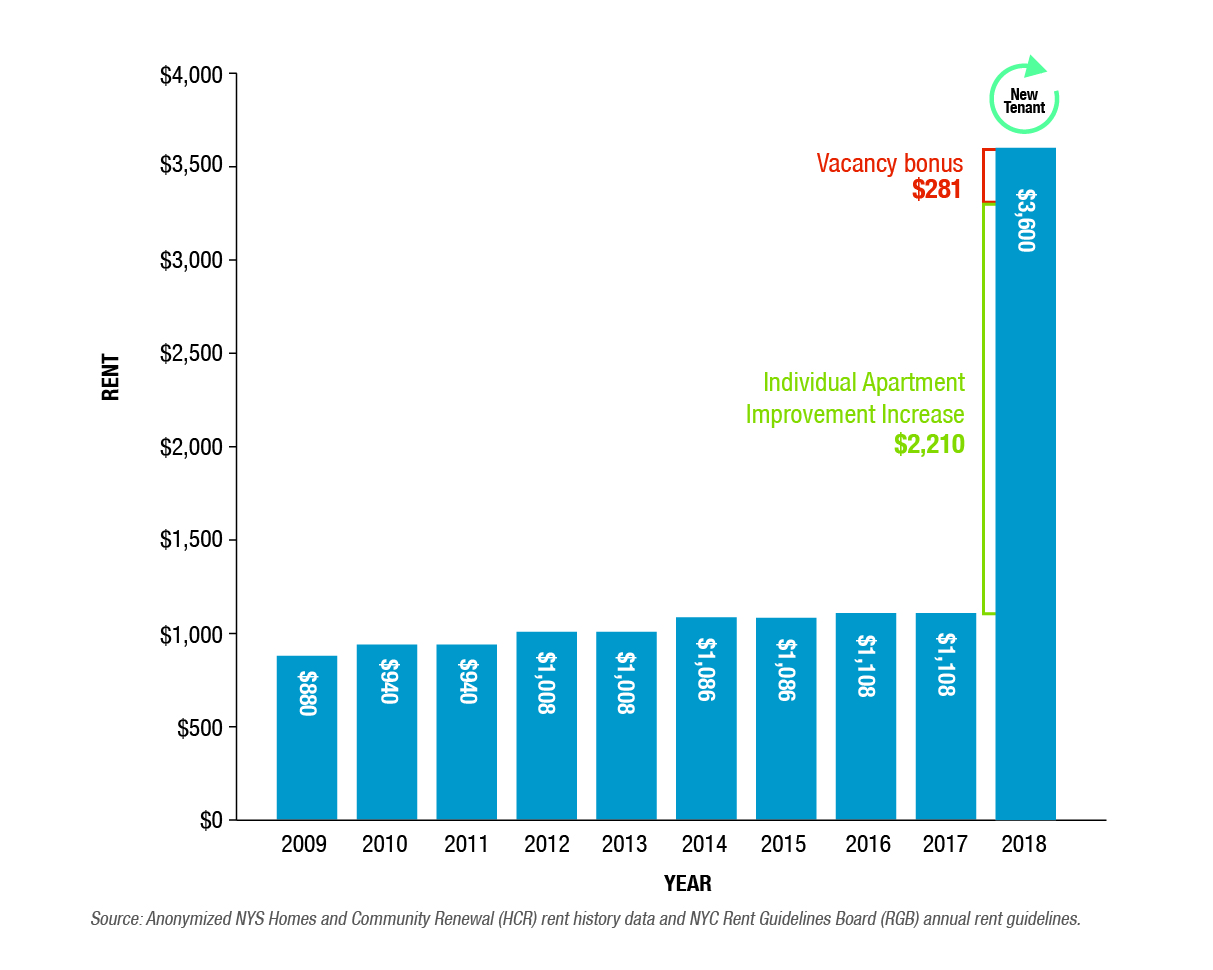

Figure 5. Rent law loopholes work in tandem to hike up rents: preferential rent + vacancy bonus

Figure 6. Rent law loopholes work in tandem to hike up rents: IAI + vacancy bonus

Outcomes for stabilized tenants, particularly those who are low-income, are getting worse. The major culprits for this are the vacancy bonus, Major Capital Improvements (MCI), Individual Apartment Improvements (IAIs), preferential rents, and vacancy decontrol. These loopholes all work in tandem to push out low-income tenants and undermine neighborhood-level stability because they erode the effectiveness of the rent stabilization system.

Figure 5 is a visualization of a real rental history for a one-bedroom apartment in Pelham Parkway in the Bronx, illustrating how vacancy bonuses and preferential rents work together to functionally destroy renter protections. Since 2007, the landlord was able to claim four vacancy bonuses in a row, creating a $1,111 gap between the preferential and legal rent. Because the preferential rent is revocable, the tenant is functionally not protected by rent stabilization laws. If the landlord decides they want the tenant out, they can hike up the rent by $1,111 at the end of their lease term.

The landlord also does not have to follow the annual RGB guidelines when setting the rent. In 2017, even though the RGB issues a 1.25 percent rent increase guideline, the landlord legally raises the rent by 7 percent. If the market continues to heat up in the neighborhood, the space between the red line (legal rent) and the blue line (preferential rent) will continue to narrow.

Figure 6 illustrates a rental history in a Bedford-Stuyvesant apartment where the landlord was able to claim a vacancy bonus, increasing the vacancy rent by $281.The owner claimed an additional $2,210 Individual Apartment Increase (IAI). Even though the RGB issued a rent freeze in 2017, this apartment’s rent went up by 225 percent, to $3,600, making it eligible for permanent deregulation.

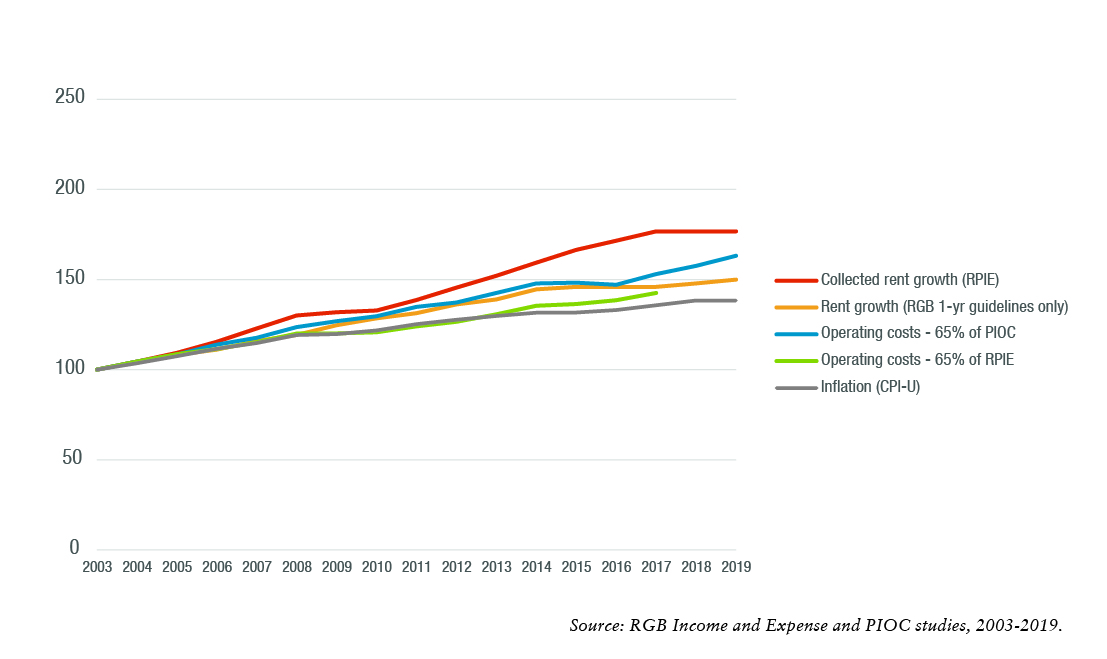

Figure 7: Operating costs vs. rents in stabilized buildings

As rent burdens among tenants increase, landlords are continuing to generate revenue on stabilized buildings. According to the latest RGB Real Property Income and Expense (RPIE) analysis, landlords of stabilized buildings spent about 59 cents out of every revenue dollar on operations, thus generating 41 cents in income.vi Historically, operational expenditures have fluctuated from 59 to 65 cents.

As illustrated by the dark blue and pink lines in the graph above, RGB’s annual rent guidelines have, over the years, tracked closely to about 65 percent of the Price Index of Operating Costs (PIOC) cost projections. These escalations provide landlords with enough revenue to operate a rent stabilized building while generating a profit.

After the rent freezes in 2015 and 2016, rent growth that can be attributed to RGB’s one year rent guidelines fell below the PIOC cost projections. But, at that point, it began to track with the average cost of operating expenditures.

As illustrated by the red line figure 7, collected rent growth, which accounts for both one and two year leases and increases above RGB’s annual guidelines, has far outpaced both cost projections and operating expenditures. Collected rent growth has risen more quickly than RGB’s annual rent guidelines, because of rent law loopholes.

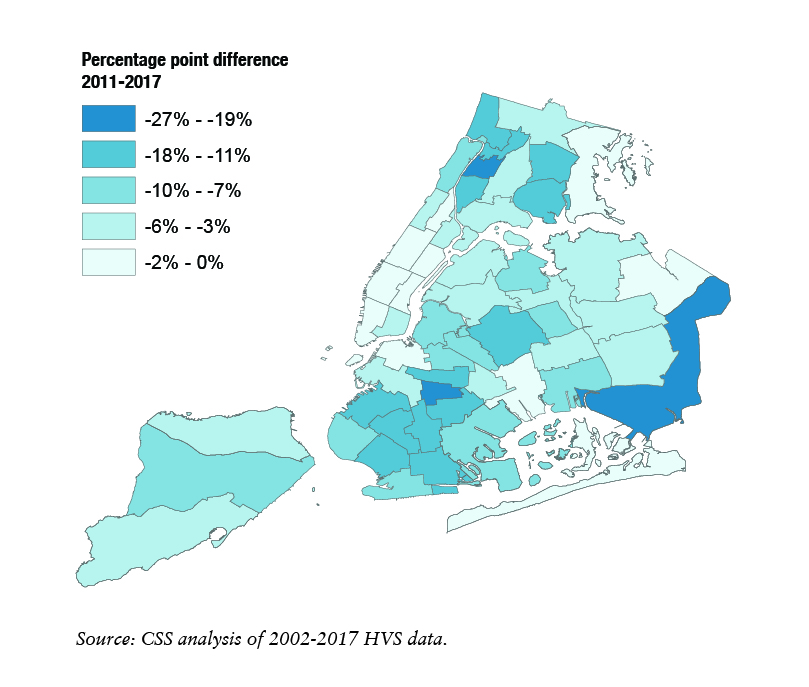

Figure 8. Major losses of low-rent units in NYC

City-wide, the share of unassisted low-rent apartments (approximately $900 in 2011 and $990 in 2017) fell from 21 percent to 14 percent between 2011 and 2017, from 445,000 to 300,000 units.vii Low-rent apartments are disappearing both because of the destructive impact of rent law loopholes on rental submarkets in the Bronx, upper Manhattan, and central Brooklyn, as well as the loss of unregulated low-rent units in low-density neighborhoods of Queens, Staten Island, and outer Brooklyn.

i Affordable to households earning 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold.

ii As a result of both rising incomes among existing tenants and tenant turnover.

iiiBecause of unavoidable inconsistencies and inaccuracies in respondent reporting of household income and contract rent, this analysis of rent burdens is based on a sub-sample of renter households. CSS subsample parameters include: rent-paying households only, excluding rent-free and owned housing; households with a positive HVS contract rent burden; households within the middle 90 percent of the income and rent distributions.

iv Selected Initial Findings of the 2017 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey, Table 7. Low-rent = under $999.

v Coalition for the Homeless analysis of NYC Department of Homeless Services and Human Resources Administration and NYCStat shelter census reports.

vi NYC Rent Guidelines Board, 2019 Income and Expense Study, April 4.

vii Affordable to households earning 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold.