Testimony to the NYC Council Committee on Housing and Buildings on Property Vacancy and Neglect

Oksana MironovaSamuel Stein

Thank you to the New York City Council’s Committee on Housing and Buildings for holding a hearing on property vacancy and neglect. Our names are Oksana Mironova and Samuel Stein, and we are senior policy analysts at the Community Service Society of New York (CSS), a leading nonprofit organization that promotes economic opportunity for New Yorkers. We use research, advocacy, and direct services to champion a more equitable city and state, including to urgently address the effects of the city’s housing affordability crisis.

CSS is over 175 years old and has been at the forefront of advocacy for better housing conditions since the beginning, from the city’s first tenement laws in the 1800s to contemporary organizing for stronger code enforcement.

Today, we would like to offer our support for Intros # 195 and 352, as well as Reso # 563. We are also here to underscore that rent regulation, as a housing policy, does not cause vacancy or housing neglect; actions by unscrupulous landlords and speculative investors do.

Landlords are fearmongering about housing neglect to gut rent regulation

In 2019, the New York State legislature passed the Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act (HSTPA), which strengthened the state’s rent regulation system by closing landlord-friendly loopholes. This law has acted as a stabilizing force during a pandemic-driven resurgence of speculation on multifamily properties. According to the latest data collected by New York City’s housing agency, the median monthly rent in rent regulated units was $1,400, $425 lower than in unregulated rentals.

In order to undermine the HSTPA, landlord lobbyists have resurrected the mythical connection between rent regulation and housing abandonment and neglect, grounding their arguments in fuzzy math and false readings of New York City’s history.

In fact, time and time again research has shown that rent regulation does not lead to property neglect. For example, New Jersey is a good place to test the impacts of rent control policies, because the state has a range of municipalities with and without rent regulation. Using a sample of 161 communities in New Jersey, a 2015 study published in the journal Cities tested the impact of rent regulation (both its presence and its relative strictness) on housing quality and foreclosure rates (as a proxy for abandonment). It did not find any significant impact on the two variables when controlling for apartment size, income, race, and median rents. [1]

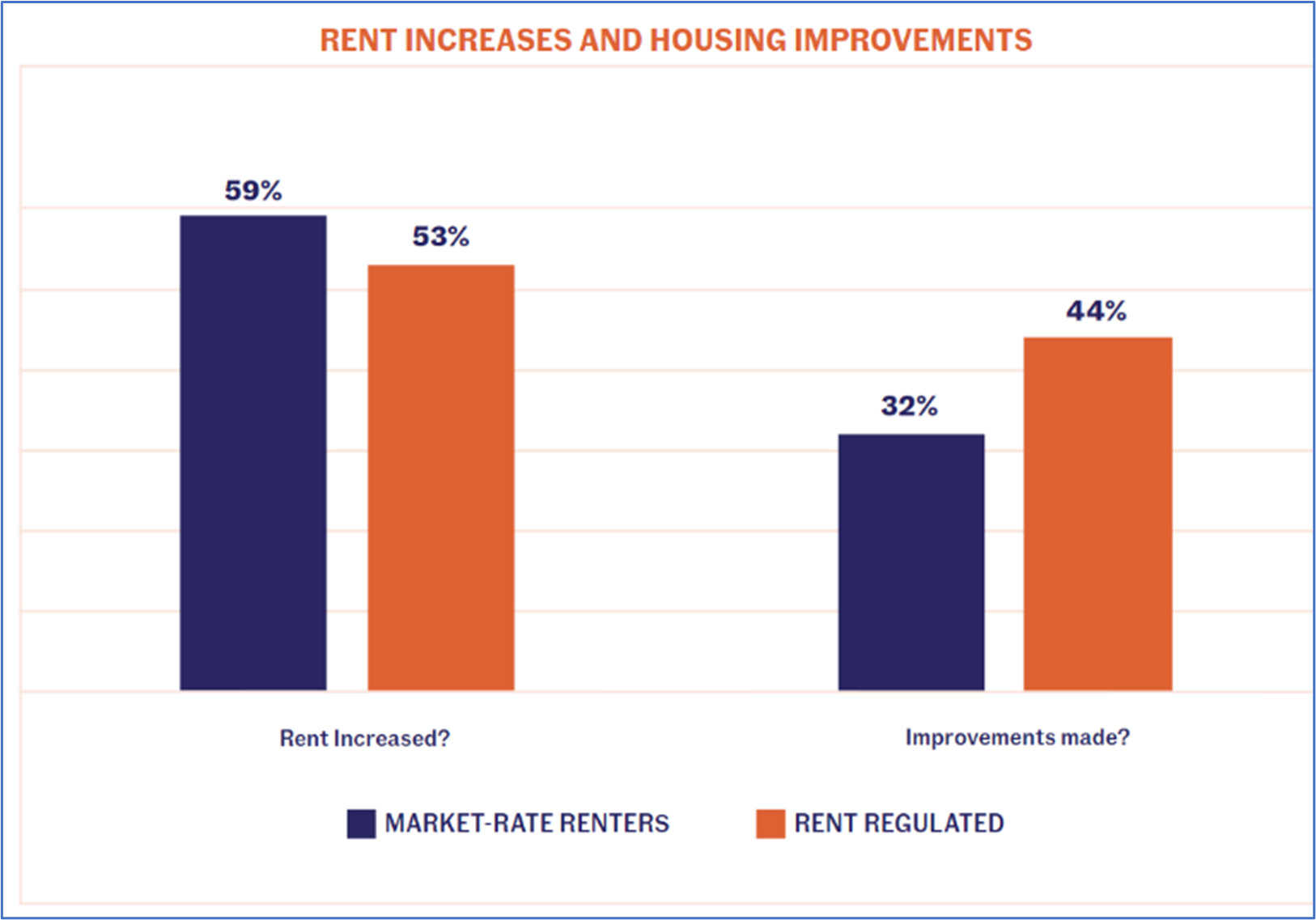

Current data from New York City also does not show any relationship between stronger rent regulations and worsening building conditions. In 2021, the NYU Furman Center analyzed HPD complaint data through the beginning of the pandemic, and found that their seasonal pattern did not change after HSTPA’s passage. Last summer, CSS polled New Yorkers about a wide range of issues, as part of our annual Unheard Third survey. We asked respondents if their rent went up in the past year, and, if so, whether the landlord had made any improvement to their apartment or building. We found that rent regulated tenants (44 percent) who experienced a rent increase were 12 percentage points more likely to see improvements in their buildings compared to unregulated tenants (32 percent).

Figure 1. Rent Regulated tenants in New York were more likely to see increases in their rent connected to improvements in their homes.

While these numbers should be far higher for any tenants experiencing rent increases, they point to an important fact: rent stabilized landlords seem to be more likely to invest in improvements than market-rate landlords. Counter to anti-regulatory arguments, rent regulation does not inhibit building maintenance. Instead, it incentivizes it, by making a portion of the rent increase contingent on apartment or building improvements.

Given ample empirical evidence to the contrary, why are landlords dredging up tired myths about rent regulation and vacancy? To bully state and local officials to undermine rent stabilization.

Are landlords willfully admitting to withholding viable units off the market?

We know from tenant testimonies that landlords in some high-cost neighborhoods with large concentration of rent stabilized units, like the Lower East Side and the Upper West Side, are purposely holding units off the market, either to combine apartment and set high rents (“Frankensteining”) or to wait out the existing rent regulation regime in the hopes that by willfully worsening the housing crisis, the legislature will grow weary and relent to landlords’ calls to weaken tenants’ rights.

In New York City, vacancies are far more prevalent in high-rent than low-cost housing. On the one hand, an over-production of luxury housing has led to a supply glut; on the other hand, many buyers of luxury property have no intention of ever really living in them, using them instead as pieds-à-terre or as pure investment vehicles.

Some in the real estate industry have said explicitly that they are not renting vacant units because, under current regulations, it costs more than they are willing to pay to upgrade them. If they are, in fact, admitting to withholding otherwise affordable rentals from potential tenants, it reflects an act of politically motivated sabotage to further worsen the housing emergency and undermine hard-fought tenants’ rights in New York.

Landlords claiming that renovations of units held off market would cost an average of $80,000 are significantly overstating the average costs of renovation at turnover. A two-minute conversation with a contractor, or elemental googling skills, will show this to be an astronomical figure. Responsible operators of rent-stabilized housing tend to average $15,000 in renovations at turnover, which matches the way the post-HSTPA Individual Apartment Improvement (IAI) guidelines are written. In rare cases where the need for rehabilitation is immense, renovation costs can reach $30,000. The only way that an $80,000 renovation pencils out is if the goal is to turn a formerly affordable unit into a luxury one.

Meanwhile, the City of New York has several programs available to landlords who need money to bring apartments up to code. For years, HPD’s Landlord Ambassador program has offered both capital and human resources to owners facing such a predicament. More recently, the city’s Unlocking Doors program offers landlords $25,000 for renovations in long-vacant low-cost apartments. In exchange, the landlords must agree to rent to a voucher-holding tenant. Because the city already offers a $4,500 bonus to landlords who accept CityFHEPS vouchers, this payout is closer to $30,000. This is a sensible way to approach the problem: landlords get the money they need to repair units; homeless households get a place to live; and the cost to the city for the voucher is lower than it would be if it were subsidizing a tenant living in a more expensive apartment. And yet landlord lobbyists have urged landlords to reject the payments and instead hold out for legislation that would deliver massive rent increases.

Close loopholes and strengthen enforcement

Rather than bending to landlords’ will, city legislators should:

- Conduct an audit to develop an evidence-based picture of the vacancy problem market-wide.

- Create a commercial and residential vacant property registry, with publicly available data (Councilmember Restler’s Intro #352).

- Use the city’s existing code enforcement system to speed up inspections of vacant units and enforce habitability standards in those apartments (Councilmember Rivera’s Intro # 195)

- Support the city’s commitment to match landlords who are truly struggling to afford repairs with renovation grants and voucher-holding tenants.

- Support the State legislature in closing the Frankensteining loophole (NYS bill S2980/A6216)

If you have any questions, please contact Oksana Mironova and Samuel Stein at omironova@cssny.org and sstein@cssny.org.

[1] Ambrosius, Joshua D., John I. Gilderbloom, William J. Steele, Wesley L. Meares, and Dennis Keating. "Forty years of rent control: Reexamining New Jersey’s moderate local policies after the great recession." Cities 49 (2015): 121-133. See also CSS’s “The Truth About Good Cause & Housing Supply.”