Testimony: Rent Stabilization Works: The Case for Re-Regulating Rents in Massachusetts

Samuel SteinOksana Mironova

Thank you to the Massachusetts Law Reform Institute for inviting us to speak on the merits of rent stabilization in Massachusetts. Our names are Samuel Stein and Oksana Mironova, and we are senior policy analysts at the Community Service Society of New York (CSS), a leading nonprofit organization that promotes economic opportunity for New Yorkers. We use research, advocacy, and direct services to champion a more equitable city and state, including to urgently address the effects of the city’s housing affordability crisis.

CSS is over 175 years old and has been at the forefront of housing advocacy since the beginning, from the city’s first tenement laws during the Progressive Era to the expansion of local housing vouchers just last week. CSS has supported rent regulation since its inception in New York over one hundred years ago and continues to fight for the strongest protections possible for tenants.

Across the country, rents are rising far faster than wages, putting tenants in an untenable position. There are many ways to combat this problem, but one essential element must be regulating rents to bring them in line with the cost of operating housing, rather than allowing them to float ever upward on the fumes of speculation and market exuberance.

A well-functioning rent regulation system provides four benefits to tenants and communities.

Benefit #1: Affordability

Rent stabilization’s most direct benefit is keeping rent inflation in check. On the neighborhood level, it acts as a counterbalance to gentrification and as a bulwark against displacement and homelessness, helping residents stay in their apartments. In tight housing markets, where the majority of low-income renters are rent burdened, limits on unscrupulous rent increases and the right to a lease renewal are paramount.

In New York City, rent regulation has acted as a stabilizing force during a pandemic-driven resurgence of speculation on multifamily properties. According to the latest data collected by New York City’s housing agency, the median monthly rent in rent regulated units was $1,400, $425 lower than in unregulated rentals. More strikingly, asking rents in unregulated apartments in Manhattan have reached an average of $4,000. This is far out of reach for poor, moderate-, and middle-income New Yorkers.

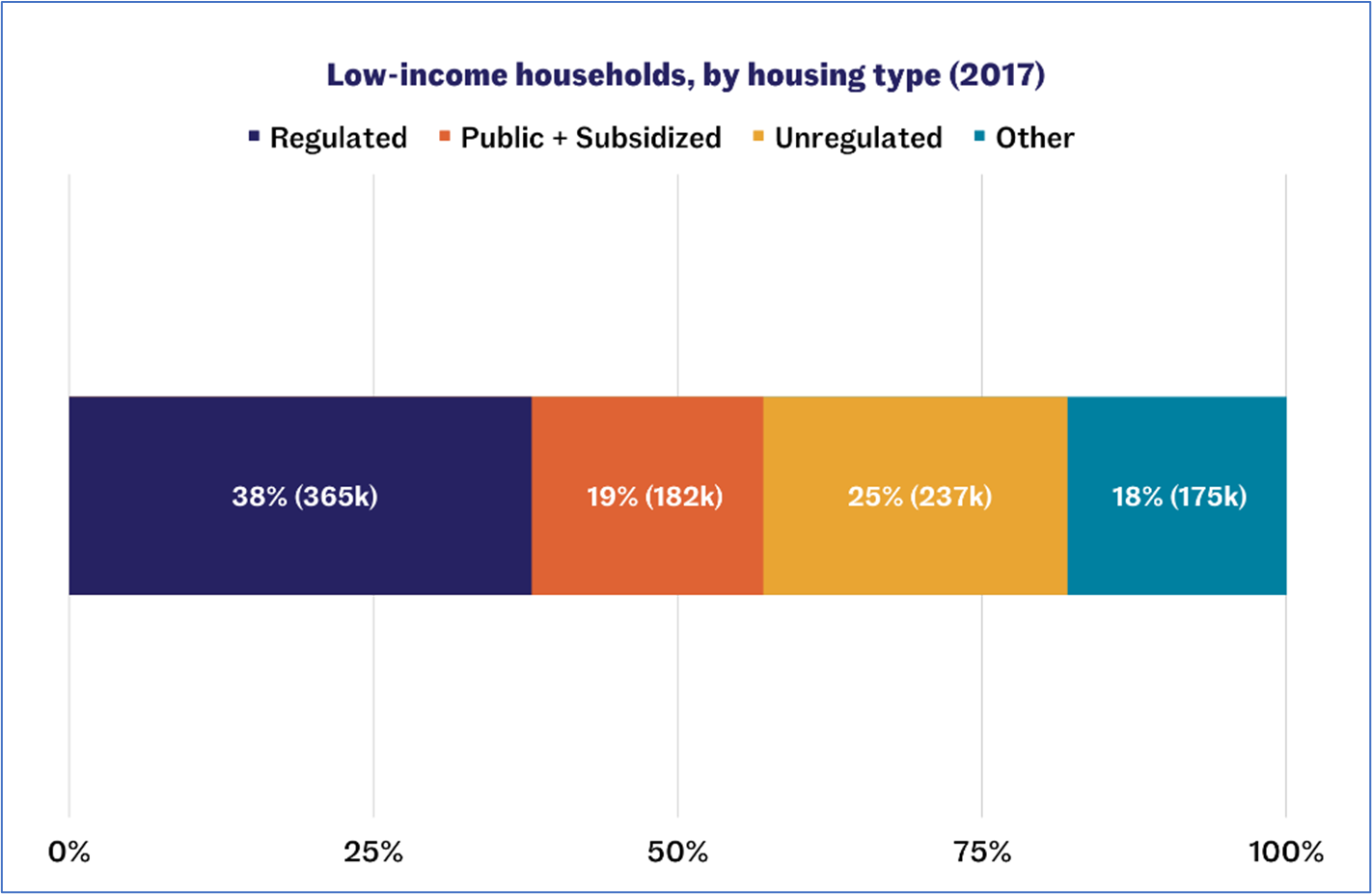

Even though rent regulation is not a subsidy program, it helps stretch public subsidy dollars. By preventing rent inflation, it makes one-time emergency rental assistance grants and housing vouchers more efficient. As stated by sociologist Matthew Desmond, who advocates for a universal voucher program, “expanding housing vouchers without stabilizing rent would be asking taxpayers to subsidize landlords’ profits.” In New York City, 61 percent of voucher holders (88,900 households) live in regulated units, while only 19 percent (28,000) live in unregulated apartments, likely because the higher-priced unregulated units are not accessible to them.

Massachusetts’ own history with rent stabilization is demonstrative as well. After Massachusetts outlawed rent stabilization in 1994, rents rose quickly in both formerly regulated and never regulated units. The overall rise in property values also encouraged condo conversions, removing affordable rental units from the market. In Cambridge, inflation adjusted asking rents for two-bedrooms went up from $1,163 in 1996 to $1,700 in 2003. In neighboring Boston rents went up from $882 in 1995 to $1,600 in 2003. Meanwhile, according to a study by David P. Sims in the Journal of Urban Economics, the loss of rent stabilization did not lead to a boom in housing Fdevelopment; it just lead to rising profits for lucky landlords.[1]

Benefit #2: Stability

A second benefit of rent stabilization is that it provides tenants with security of tenure – in other words, the assurance that they can continue to live in their home without fear of arbitrary eviction or unconscionable rent hikes. Rent regulations offer tenants the right to a lease renewal if the tenant is paying rent and is not in violation of their lease. This provides renters with the stability to plan for the future.

This stability applies not only to individual tenants, but to neighborhoods as a whole. In an unregulated real estate market, buildings are bought and sold for prices based on revenues the purchaser expects to extract from the building in the future, rather than the revenue it generates in the present. Investors often pay much more for buildings than their rent rolls justify, under the assumption that they can significantly raise the building’s profit levels (or “net operating income”) by raising rents, diminishing labor and maintenance costs, or both. Without rent regulations, investors buy multi-family buildings, evict tenants, raise rents, refinance and pull equity from the building as profits rise, and eventually sell for far more than the purchasing price.

With rent regulation, building values are more closely tied to their actual rent rolls, rather than to speculators’ dreams of future profits predicated on deferred maintenance and displacement. . This keeps building and land sales prices from escalating dramatically, making building prices more accessible to purchasers who prioritize long-term neighborhood stability, including MWBE and non-profit developers, community land trusts, and even organized tenants themselves.

Benefit #3: Organizing

Rent stabilization provides tenants with the protections necessary for individual or collective action. Rent hikes and lease termination are retaliatory tools landlords can use against tenants who organize tenants’ associations or ask for repairs. If tenants know they can continue to live in their home as long as they can pay the rent, and if they know that rent won’t go up that much from year to year, then they can organize in confidence for better living conditions, hazard abatements (i.e., lead paint), accessibility improvements, and more. They can also stand up with greater confidence against illegal actions by their landlord, like failing to meet building and fire codes.

Benefit #4: Investment

Many contemporary rent regulation systems – including New York’s – contain mechanisms to help landlords pay for building improvements, beyond the standard level of maintenance and repair. In New York, landlords can use “Individual Apartment Improvement” increases to pass on in-unit repair costs to tenants and “Major Capital Improvement” increases to pay for building-wide improvements. This can act as an incentive to get landlords to continue improving their buildings. The key to making such a system fair to tenants, though, is to limit how much rent can go up based on these improvements, and to ensure that after the improvement is paid off, the rent increase goes away.

Opponents of rent regulation often claim that it will result in disinvestment from buildings and increased maintenance issues. Studies have continuously shown, however, that no such link exists. For example, New Jersey is a good place to test the impacts of rent control policies, because the state has a range of municipalities with and without rent regulation. Using a sample of 161 communities in New Jersey, a 2015 study published in the journal Cities tested the impact of rent regulation (both its presence and its relative strictness) on housing quality and foreclosure rates (as a proxy for abandonment). It did not find any significant impact on the two variables when controlling for apartment size, income, race, and median rents.[2]

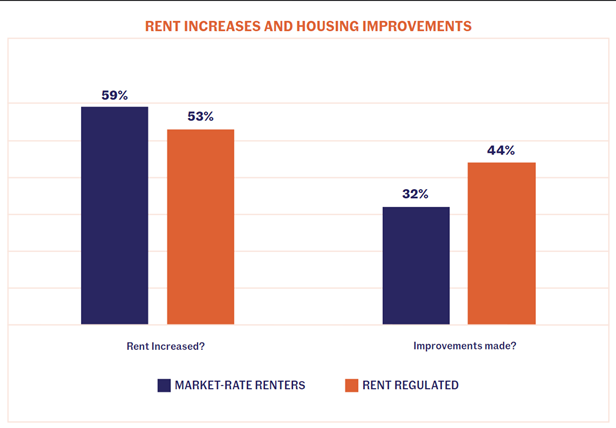

Last summer, CSS polled New Yorkers about a wide range of issues, as part of our annual Unheard Third survey. We asked respondents if their rent went up in the past year, and, if so, whether the landlord had made any improvement to their apartment or building. We found that rent regulated tenants (44 percent) who experienced a rent increase were 12 percentage points more likely to see improvements in their buildings compared to unregulated tenants (32 percent).

While these numbers should be far higher for any tenants experiencing rent increases, they point to an important fact often overlooked in the debates around rent regulation in New York, and beyond: according to our survey data, rent stabilized landlords seem to be more likely to invest in improvements than market-rate landlords. Counter to anti-regulatory arguments, rent regulation does not inhibit building maintenance. Instead, it incentivizes it, by making a portion of the rent increase contingent on apartment or building improvements.

Rent regulation not only helps tenants get the repairs and improvements their buildings need, but helps them advocate for public investment without fear of future displacement. In an unregulated rental market, when the public sector makes significant improvements to an area – like adding a new mass transit line or building a new park – nearby landlords can capitalize off of this public investment by increasing rents. Tenants understand this, and are often reluctant to call for any improvements to their neighborhoods, which could end up leading to their eventual displacement.

In a regulated rental market, private landlords can’t privatize the benefits of public investment in this way. If the city builds a new park or expands transit access, existing tenants do not have to bear rent increases capitalizing on this new local amenity and can stay in the neighborhood to enjoy its benefits. Rent regulation thus provides tenants with the security necessary for full civic participation, as renters no longer have to fear that neighborhood improvement will result in gentrification and displacement.

Rent regulation is essential

We strongly encourage the Massachusetts legislature to pass House Bill 2103 and allow cities and towns to enact rent regulations. Rent stabilization is the simplest way to extend affordability, protect tenant and neighborhood stability, support tenant organizing, and encourage building investment. It is the cornerstone of any other investments in housing affordability, making housing subsidies work better by controlling rent inflation.

In short, rent regulation is essential. While there is plenty more Massachusetts can do to stabilize rents and address the housing and homelessness crisis, none of it will be effective in the long term if it is not paired with rent regulations.

Notes

1. See also: Autor, David H., Christopher J. Palmer, and Parag A. Pathak. "Housing market spillovers: Evidence from the end of rent control in Cambridge, Massachusetts." Journal of Political Economy 122, no. 3 (2014): 661-717. The Community Service Society also recently took on this question in our brief, “The Truth About Good Cause & Housing Supply,” authored by Samuel Stein, Paul Williams, Oksana Mironova and Sylvia Morse, and published in May 2022.

2. Ambrosius, Joshua D., John I. Gilderbloom, William J. Steele, Wesley L. Meares, and Dennis Keating. "Forty years of rent control: Reexamining New Jersey’s moderate local policies after the great recession." Cities 49 (2015): 121-133. See also CSS’s “The Truth About Good Cause & Housing Supply.”