How will the candidates’ housing plans affect New York City?

Thomas J. WatersOksana Mironova

The two remaining contenders in the Democratic presidential primaries, Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders, have both put forth comprehensive housing proposals that would reshape the national housing policy landscape and bring billions of dollars in benefits to New York City.

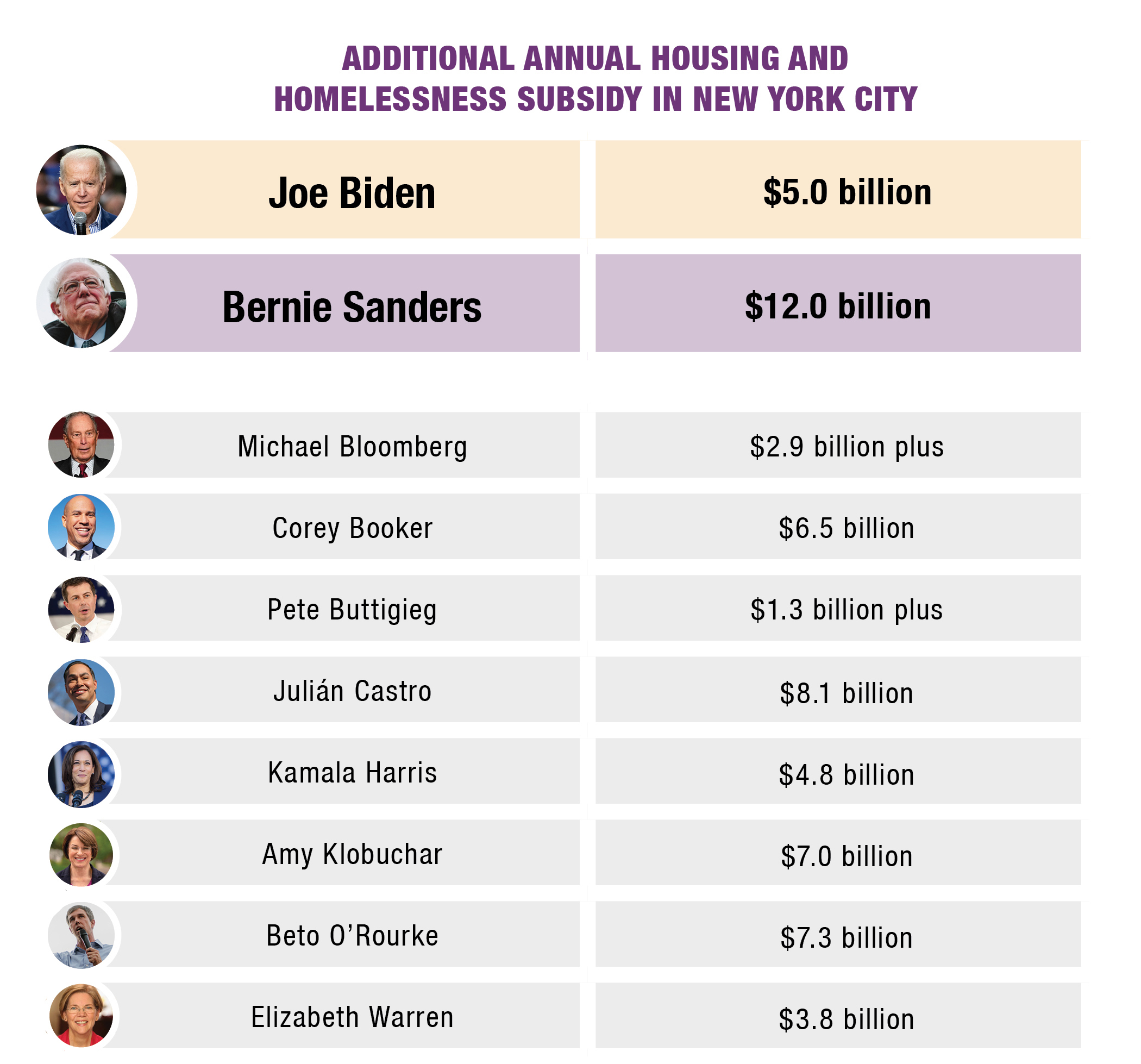

This is something that has never happened in any past primary season, but this time the entire candidate field paid an unprecedented amount of attention to housing. Many of the candidates who entered the race and then withdrew also put forth strong proposals, with Corey Booker, Julián Castro, Kamala Harris, and Elizabeth Warren setting the pace early. Eventually ten campaigns provided enough detail to at least partially estimate their dollar impact on New York City.

These plans signal an emerging consensus in the Democratic Party that housing and homelessness should be top priority issues, and that the federal government should be ready to commit to new spending programs running into the hundreds of billions of dollars. Campaign proposals generally provide only a rough guide to the policies that presidents eventually succeed in enacting, but they do provide insights into the party’s priorities and understanding of key issues.

This apparent new Democratic consensus on housing has huge implications for New York City. The candidates’ plans provide up to $12 billion a year in additional federal subsidy for new housing production, rent assistance, reinvesting public housing, and homelessness programs here, as well as new protections for tenants and mortgage borrowers, and measures to discourage exclusionary land-use rules, redlining, and other forms of racial exclusion. These sums would not only help to address the city’s entrenched housing needs, but would also provide a significant economic stimulus, especially to the city’s poorer neighborhoods.

Today the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) spends $42.6 billion on direct subsidies to build and operate affordable housing. Of that, 53 percent goes to Section 8 vouchers for tenant families to help pay their rent, 17 percent goes to public housing, and 30 percent goes to privately owned subsidized developments. In addition, HUD and other agencies spend $5.8 billion a year on various homelessness programs, the Internal Revenue Service allocates Low Income Housing Tax Credits to the tune of $9 billion a year, and the national Housing Trust Fund received $248 million last year from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

New production and preservation

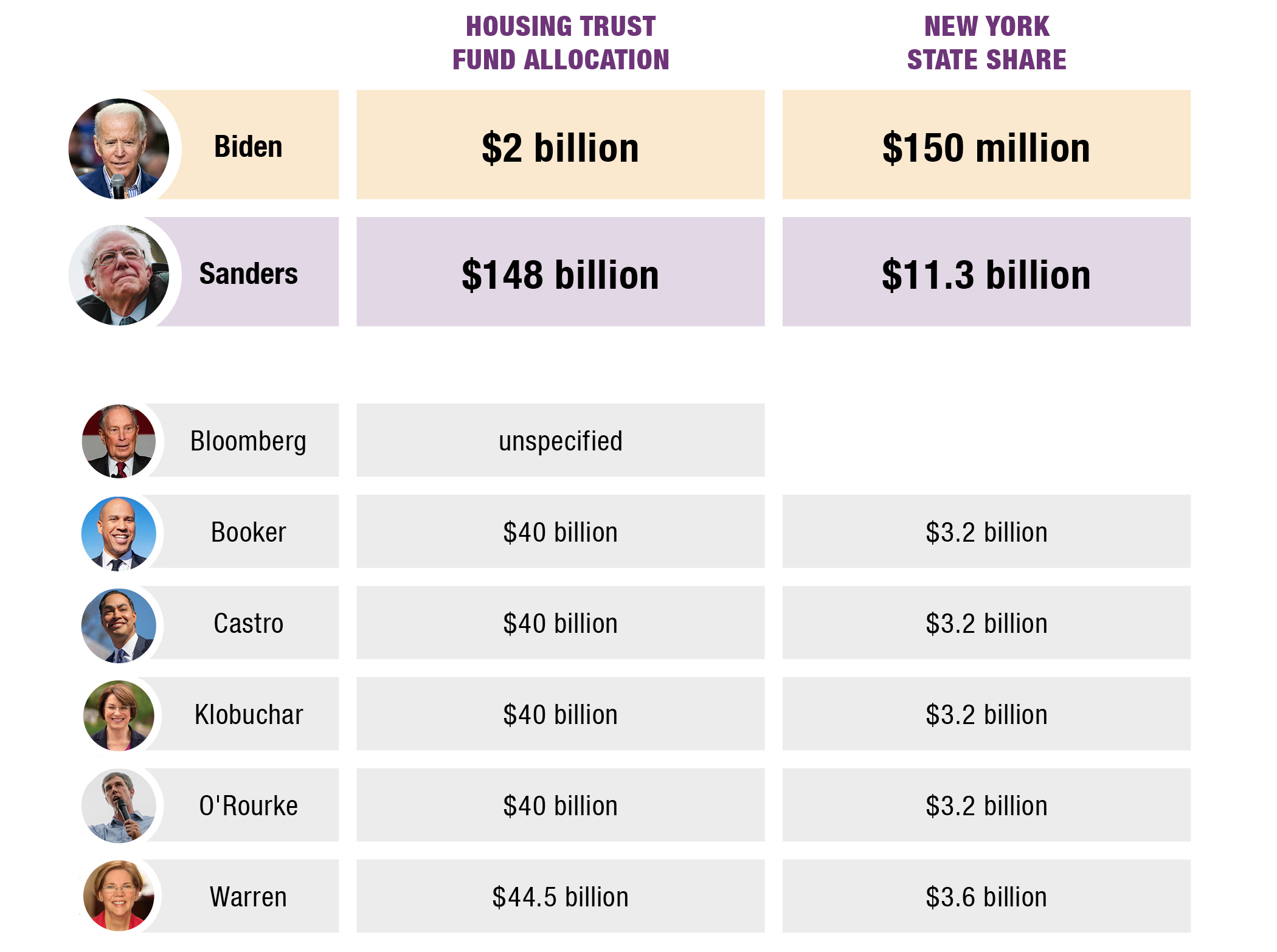

Biden and Sanders would both expand affordable housing production and preservation using the Housing Trust Fund (HTF), a welcome focus on the first new federal housing program in over 40 years to explicitly serve what the federal government calls extremely low income renters that was first funded when Julian Castro was HUD Secretary under President Obama. In New York City that translates to up to about $29,000 a year for a family of three.

Other subsidies for new housing construction, including the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) (which Biden also proposes to expand), primarily benefit people with much higher incomes. Biden’s affordable housing commitment includes $10 billion toward energy efficiency retrofits, an important intersection with climate change policy.

HTF is a block grant program: The federal government distributes funds to the states using a formula and state governments make the funds competitively available. In 2019, Congress allocated $248 million to the trust fund, which then passed on $19 million to New York State. New York City probably received about half of that statewide benefit. Thus Biden’s proposed funding commitment, though much smaller than Sanders’s, would still be a dramatic increase over the status quo.

The chart below illustrates projected HTF commitments under each candidates’ plans, and the resulting increases to the New York State share.

In New York, both the governor and the mayor have been criticized for failing to meet the need for deeply affordable housing. A major federal commitment to extremely low-income renters would help with this goal, especially when paired with other proposals, like rental subsidy assistance proposed by both Biden and Sanders or the $50 billion grant program for community land trust development proposed by Sanders.

Rent assistance

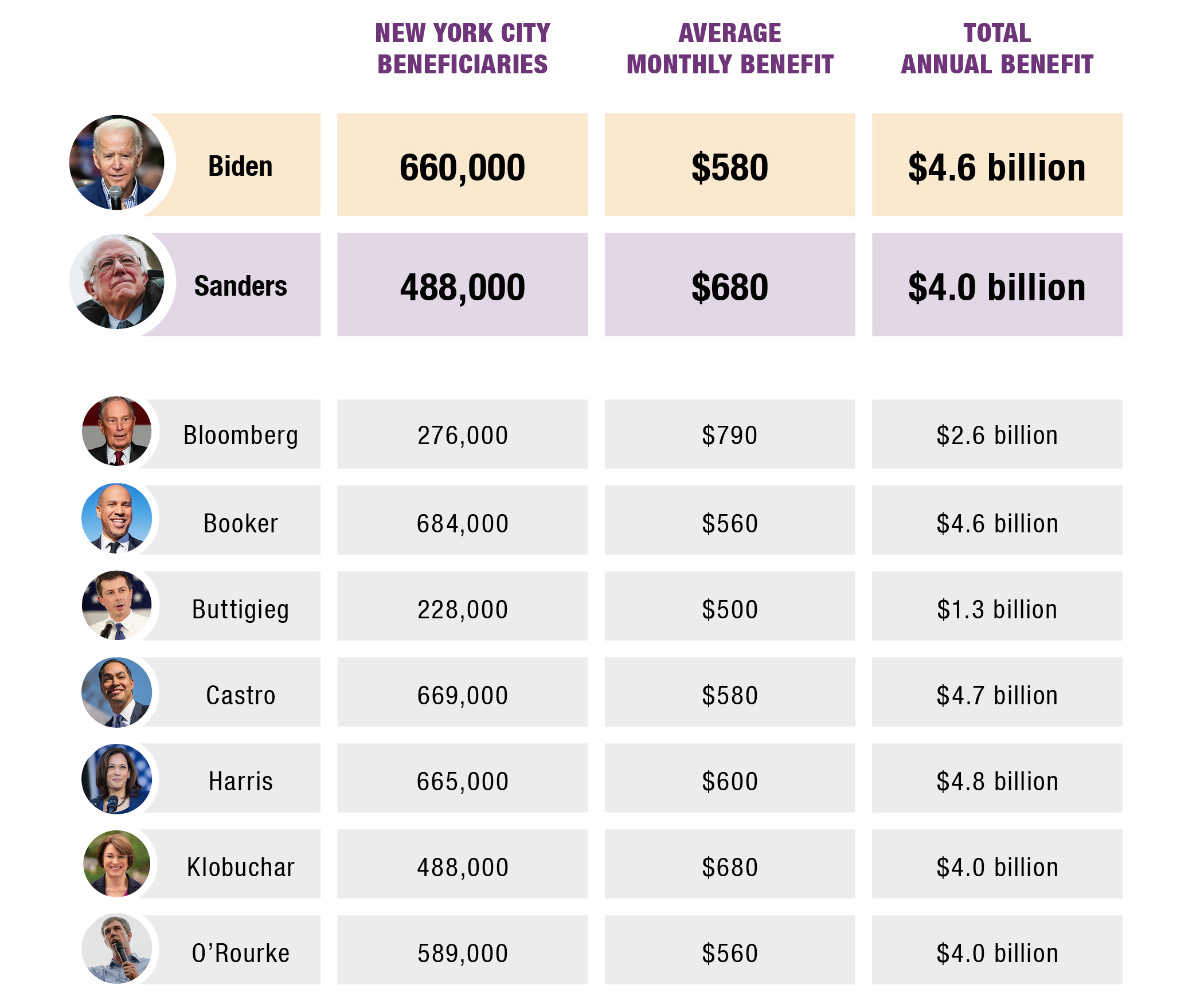

Biden and Sanders both propose to expand the federal Section 8 voucher program. Under Section 8, the federal government provides direct assistance to low-income tenant families to pay for part of their rent in private apartments. Currently only one in four income-eligible families receives a voucher, but both candidates would increase funding so that every eligible family could be served. Many of the candidates who have dropped out also proposed to expand Section 8, sometimes to a lesser extent.

Biden would add another kind of rent assistance in the form of an income tax credit for families with somewhat higher incomes who nevertheless pay unaffordable rents – and idea first put forward by Kamala Harris and also embraced by some of the other former candidates. The income limit for Section 8 is $48,000 for a family of three in New York City, while Biden’s tax credit would go to families up to $77,000. Both programs would pay for the portion of tenants’ rent remaining after the family contributes 30 percent of its income.

Because New York City has more than 700,000 households in unsubsidized housing paying more than 30 percent of income in rent, it stands to benefit greatly from any of these plans. There are already 104,000 of these households on waiting lists for the city’s existing stock of Section 8 vouchers.

The city’s very tight housing market could present problems for this approach, however. Already, many families that receive Section 8 vouchers are unable to find an apartment that meets the program’s conditions where the landlord will accept them. Expanded rent assistance programs would work best when combined with expanded affordable housing production programs – something both candidates already propose.

The Sanders plan would provide rent assistance worth $680 a month to an additional 488,000 families in New York City, for a total of $4 billion a year. The Biden plan would do the same, plus add smaller benefits through a tax credit for 172,000 somewhat higher-income families, totaling $4.6 billion. (We base these estimates on CSS analysis of the Census Bureau’s New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey.)

Public housing

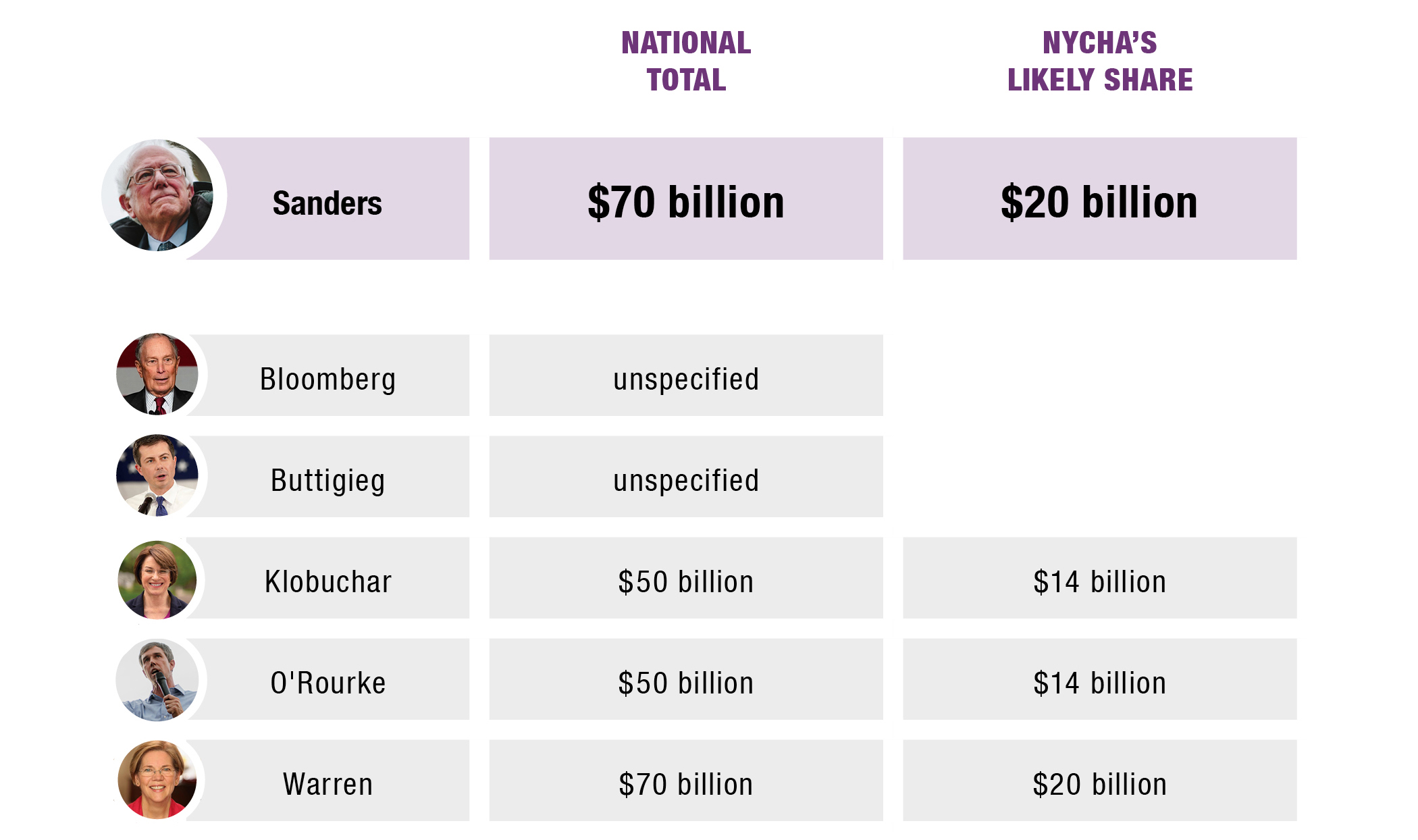

One important difference between the Biden and Sanders proposals is that only Sanders includes significant new funding for the capital needs – long-delayed major repairs – of the country’s existing stock of public housing.

Public housing across the country receives about $7.4 billion a year in federal money, an inadequate amount that contributes to deteriorating conditions. The poor physical condition of much of the country’s public housing developments, together with the poverty of the residents, may explain why so many politicians are reluctant to embrace public housing, but the program urgently needs capital funding.

Today, the New York City Housing Authority estimates its capital needs at $40 billion over the next five years, based on actual survey of the condition of its properties. The best estimate for the total national need is $70 billion, but that is based on extrapolations from surveys of a sample of housing authorities in 2010 and it appears to include only $20 billion for NYCHA. Nydia Velázquez, congressional representative for parts of Brooklyn, Lower Manhattan, and Queens has also introduced legislation that would allocate $70 billion for public housing capital repairs.

In addition to proposing $70 billion in capital funding for public housing, Sanders also joined Representative Ocasio-Cortez in introducing the Green New Deal for Public Housing Act, which would invest $119 to $172 billion in public housing green retrofits over 10 years.

These are not annual appropriations but total capital amounts, which would be appropriated over a period of years. The annual totals presented above assume that the funding under Sanders’s proposal would be spread over ten years, and they do not include funds from the Green New Deal.

These proposals would not only help improve living conditions for NYCHA residents, they could also reduce the housing authority’s reliance on controversial means of raising money, such as partial privatization or building market-rate housing on public housing campuses.

Ending homelessness

The Biden and Sanders campaigns both explicitly address homelessness in their housing proposals, relying primarily on the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance program as the funding mechanism. McKinney-Vento provides funding to localities, states, and public-private partnerships for homeless services, shelters, supportive housing, rent subsidies, and permanent housing. Under the McKinney-Vento umbrella, HUD distributes funding through a number of programs, including the formula-based Emergency Solutions Grant and competitive Continuum of Care program. Some former candidates favored one-time allocations, like Pete Buttigieg’s $3 billion emergency funding package to address street homelessness in highly impacted cities.

In 2018, Congress allocated $2.4 billion for McKinney-Vento and New York State received $240.6 million. Biden and Sanders have proposed expanding funding for outreach and social services, and Biden has committed to developing a national homeless strategy, rooted in the Housing First model, withing his first 100 days in office. Permanent supportive housing emerged as a central tool for addressing the national homelessness crisis among many candidates who have since withdrawn as well, including Michael Bloomberg, Castro, Buttigieg, and Amy Klobuchar.

The chart below illustrates projected increases to funding for housing to address homelessness under the various campaign proposals, and the resulting increase in the New York State and New York City shares.

These commitments would significantly expand local capacity to address the city and state’s growing homeless population: there are 92,000 homeless people statewide and 78,700 in New York City. For example, expanded federal funding can help sustain a proposed rental assistance program like Home Stability Support, and the development of new, deeply affordable housing statewide.

Tenant protections

The Sanders, and to a lesser extent, Biden campaigns include proposals to bolster renter protections. Long framed as a local policy realm, proposals that provide federal funding for the implementation of tenant protections are a welcome sign and could lead to increased resources for New York.

The Sanders campaign calls for the establishment of a $2 billion national fund to support local right to counsel laws, which would guarantee low-income tenants facing eviction the right to legal representation in housing court. Biden promises to enact the Legal Assistance to Prevent Evictions Act of 2020, which would provide federal funding for legal assistance in eviction cases and to establish a renter bill of rights. Federal funding for local right to counsel implementation was also a feature of the Booker, Bloomberg, and Castro campaigns.

The Sanders campaign draws connections between exclusionary zoning ordinances and anti-renter laws (such as rent control pre-emption),calling for a new HUD office that would channel funding to states and localities that strengthen tenant protections and implement fair and inclusive zoning ordinances. The Sanders campaign also calls for a national just cause eviction law and rent increase cap. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the Congressional representative from the East Bronx and northern Queens, has proposed similar legislation. Among candidates that have since withdrawn, Warren and Klobuchar both committed infrastructure funding to incentivize local adoption of tenant protection laws.

New York serves as a model for a number of the above-mentioned proposals. Federal funding can help offset the implementation of the city’s existing right to counsel law, which cost $30 million in 2019 (and will become more expensive as the program is expanded to include more tenants), or provide additional funding to the State’s woefully underfunded Tenant Protection Unit, tasked with detecting fraud and harassment in the state’s rent regulation system.

At the same time, not all of New York City’s, much less New York State’s, tenants are universally protected. Federal funding may be the push necessary for the State to pass a just cause eviction law, which would protect an additional 1.6 million households who are currently vulnerable to arbitrary evictions. The Sanders campaign’s call for national rent control and a just cause mandate would expand renter protections statewide, without the need for politically difficult campaigns in certain jurisdictions.

Racial justice through housing policy

Acknowledging the role the federal government played in exacerbating segregation and widening the racial wealth gap, both Biden and Sanders have called for the expansion of tools to prevent ongoing housing discrimination including strengthening the Fair Housing Act and other fair housing provisions, banning source of income discrimination,, and discouraging exclusionary zoning. Biden’s campaign also committed to protecting the Community Reinvestment Act and creating a credit reporting agency within the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, as a public alternative to private credit reporting.

Before suspending their campaigns, Harris and Warren proposed major down-payment assistance programs for households living in historically redlined communities. Harris’s $100 billion program would have provided $25,000 grants to first time homebuyers who have lived in formerly redlined neighborhoods for at least 10 years. Warren’s program would have provided loans equal to 3.5 percent of the assessed home value for first time homebuyers living in historically redlined or high poverty areas for at least 4 years. Buttigieg proposed a blend of a public land bank and homeownership assistance program, which would have created a federal public trust that would have purchased vacant properties in target cities and provided them to means-tested residents.

The top Democratic presidential candidates have produced innovative and formidable proposals for alleviating a growing housing affordability crisis. The candidates should explore these ideas further during one of the upcoming debates. And whoever ends up getting the nomination – and whoever is ultimately elected – should consider these proposals as a basis for rethinking the federal government’s role in addressing U.S.’s national housing crisis.

The Community Service Society is launching Housing the Unheard Third, a blog series that will include discussions of latest housing policy debates, original analysis, and deep-dives into the laws and programs that impact where and how low income New Yorkers live. This is the first post in that series.