Disconnected: The Digital Divide & Disrupted Schooling in NYC

Patrick JosephIrene Lew

Context

Unequal access to the internet and digital devices, or the “digital divide,” has been documented for decades. In the late 1990s, when internet and computer technology proliferated in the United States, researchers recognized a gap in access to such technologies along socioeconomic lines, with wealthier populations having more access to these technologies than their less wealthy counterparts.[1] Though overall access to high-speed internet and digital devices has increased over the years, there remain stark differences in accessibility between higher-income and lower-income households. A 2021 survey from The Pew Research Center found that just 57 percent of U.S. adults with incomes below $30,000 had broadband service at home compared to 83 percent for households with incomes between $30,000 and $99,000 and 93 percent for households with incomes above $100,000.[2] Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 37 percent of households in New York City earning less than $20,000 a year lacked an internet subscription, seven times higher than the share of households earning more than $75,000 a year who lacked an internet subscription (5 percent).[3] The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these disparities in access to reliable broadband internet, which suddenly became a necessity for working and learning effectively. In this brief, part of the series Whose Recovery? Addressing the Needs of Low-Income New Yorkers, we provide an overview of key findings from our 2021 Unheard Third survey on the digital divide in New York City.

Key Findings

- Households in the Bronx were most likely to report difficulties with internet access at home compared to other boroughs. Nearly a quarter of Bronx respondents reported that their household lacked home internet access in the past year, double the share of Brooklyn and Queens respondents. One out of every four Bronx residents said that they had an inadequate number of digital devices at home.

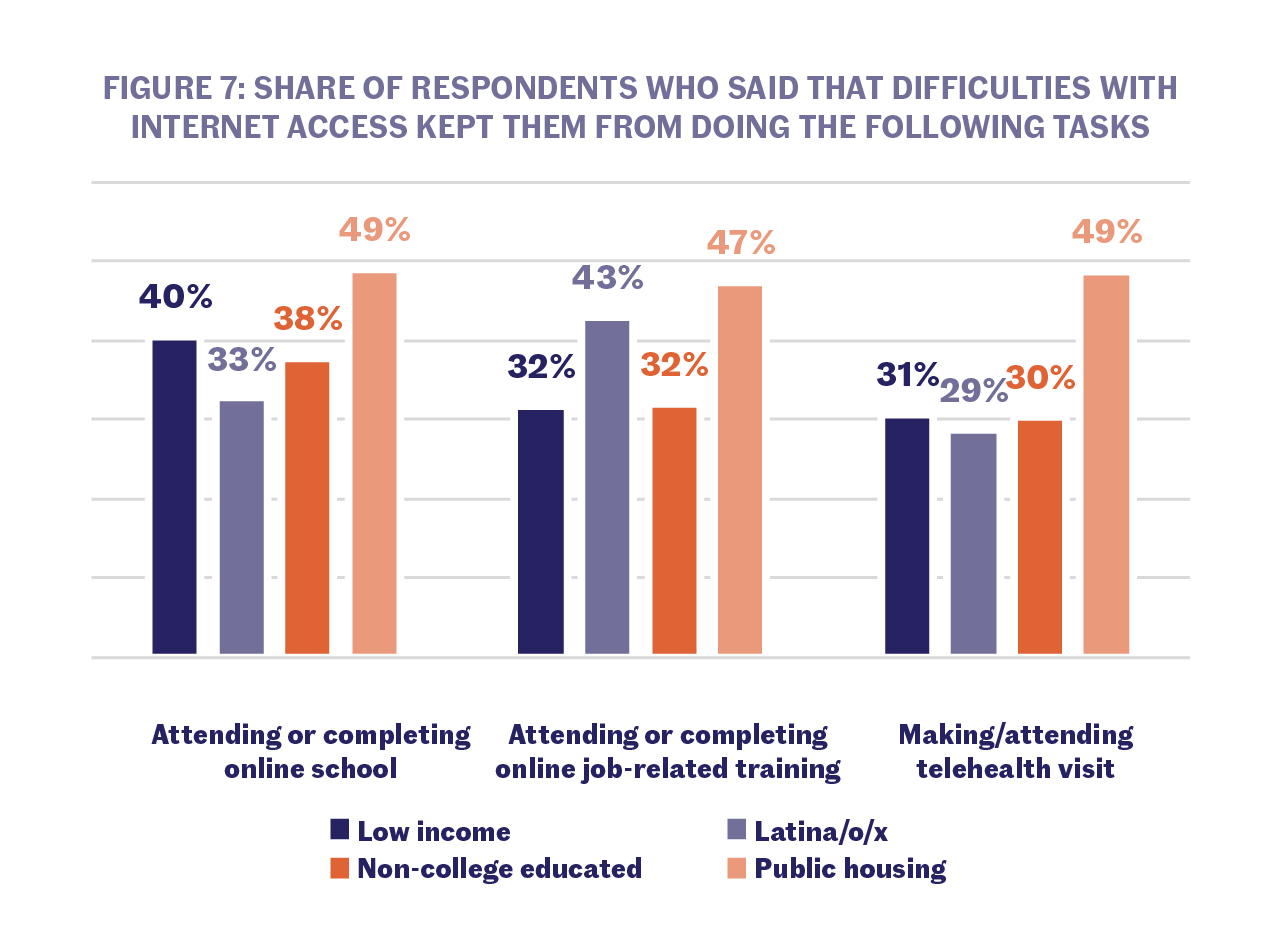

- The digital divide is preventing New Yorkers from climbing up the economic ladder. Residents in public housing have experienced even greater setbacks than the rest of New York City. Four out of every ten low-income New Yorkers reported that lack of internet access and working devices kept them from completing online schooling, and nearly a third said that this was a barrier to completing online job-related training. Nearly half of public housing residents reported that these challenges kept them from completing online education, job training, or telehealth visits.

- Across incomes, parents in NYC are deeply concerned about their children’s education prospects due to the pandemic. Nearly two-thirds (65 percent) of low-income parents surveyed said that the impacts from the pandemic will likely result in a long-lasting setback for their children’s education. Among low-income parents, a staggering 74 percent of Latina/o/x parents said that the pandemic will likely result in a long-lasting setback for their children’s education.

Summary of Recommendations

- Pilot municipal broadband in the Bronx, where the digital divide is most pronounced.

- Provide all NYCHA residents with free internet access. Our findings suggest that, while in some limited instances, internet providers are servicing NYCHA for free, this provision is not enough to offset the needs of all NYCHA residents.

- Ensure all public school students have high-speed internet access and working devices. The student demand for internet devices was not met by the Department of Education. This mayoral administration should ensure that all students have the devices and connectivity they need for schooling and should measure the extent to which students received access to devices.

- Introduce legislation to study the feasibility of municipal broadband across New York State. The state legislature should introduce legislation to study the feasibility of municipal broadband. State resources would be instrumental in improving internet accessibility in New York City and across the state.

Introduction

The digital divide has existed in our society since the introduction of personal computing and internet technologies, but the pandemic brought this divide – across income, race and ethnicity, education level, geography, housing status and beyond – into an ever-stark reality as dependence on remote work and schooling became the norm over the last two years. Though overall access to such technologies has increased over the years, there remain glaring differences in accessibility between higher-income and lower-income households. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 37 percent of households in New York City earning less than $20,000 a year lacked an internet subscription, seven times higher than the share of households earning more than $75,000 a year who lacked an internet subscription (5 percent).[4] The pandemic exacerbated these disparities in access to reliable, broadband internet, which suddenly became a necessity for working and learning effectively.

The impact of the digital divide on learning was especially pronounced as the pandemic’s disruption of New York City public schools was compounded by lack of computer and internet access. In addition to disruptions in healthcare, meals, sports, afterschool programs, and socializing opportunities that public schools provide, many students faced hardship in accessing instructional content from their teachers. Responding to the needs of their students in the spring of 2020, the New York City Department of Education (NYCDOE) worked to provide over 300,000 iPads to students (less than one third of all students in New York City’s public school system), but this effort took months to achieve and did not completely offset the need.[5] According to the NYCDOE’s 2021 report on remote learning, more than 2,500 households that requested a device did not receive one in autumn of 2020.[6]

Under New York’s constitution, all K-12 students within the state are entitled to a free education (NY Const art XI § 1).[7] However, when our public education system moves into the home and students are expected to access their education online, education comes at an expense for families. Given our findings that low-income New Yorkers, as well as Black and Latina/o/x New Yorkers, are shouldering the brunt of the digital divide, the inability of the education system to safeguard access to educational services may violate the state rights of public-school students.[8]

In this brief, part of the series Whose Recovery? Addressing the Needs of Low-Income New Yorkers, we provide an overview of key findings from our 2021 Unheard Third survey on the digital divide in New York City. This brief focuses on New Yorkers who are disproportionately impacted by the digital divide and the challenges that they face because of inequitable access to the internet.

Stark inequities in internet access and affordability by income

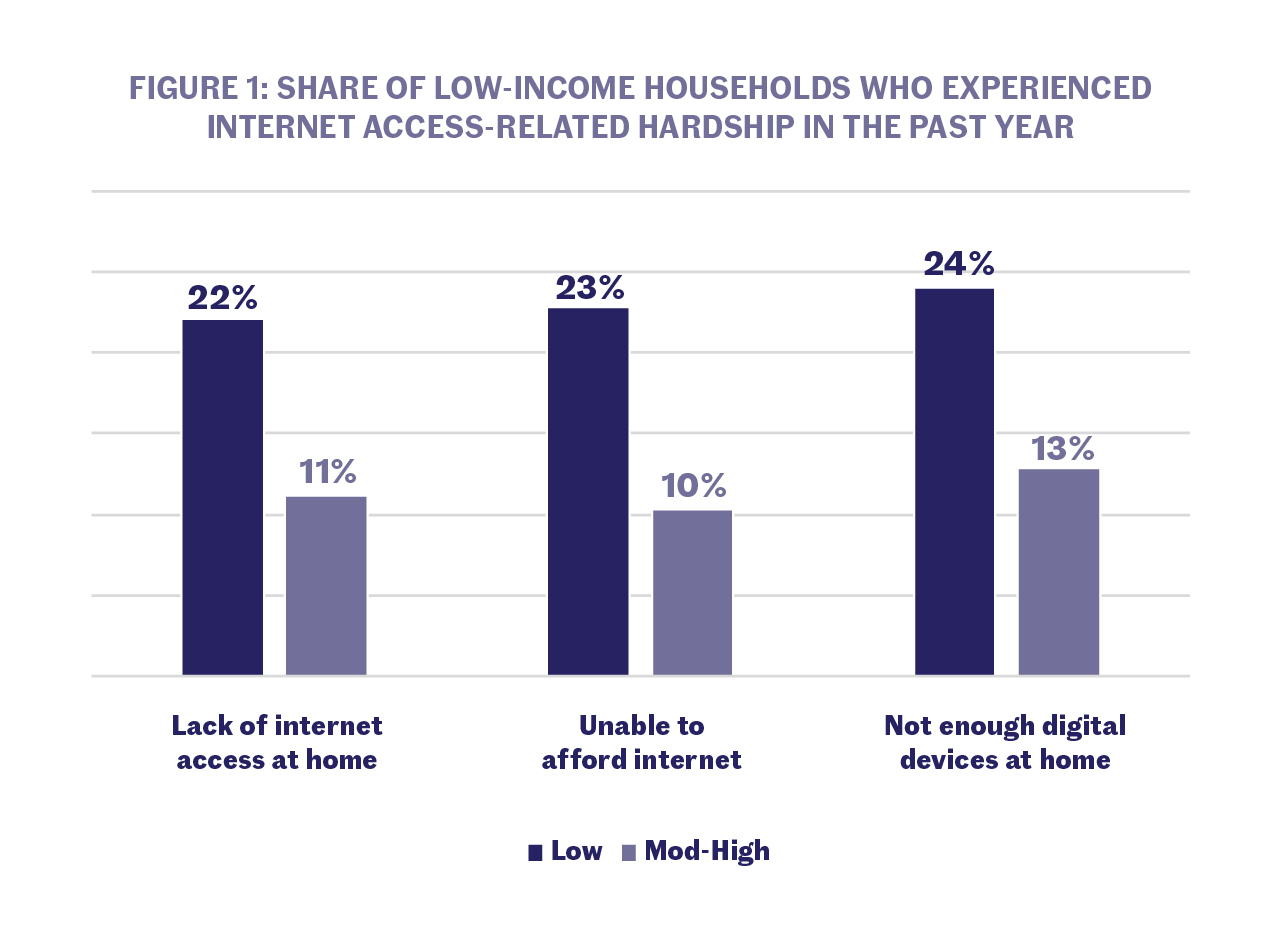

According to the 2021 Unheard Third survey, more than one out of every five low-income New Yorkers (22 percent) said that their household lacked access to the internet at home in the past year, double the share of those with moderate to higher incomes (See Figure 1). Low-income households were also twice as likely as those with moderate to higher incomes to struggle with affording internet access (23 percent of low-income households vs. 10 percent of moderate-higher-income households). Another aspect of digital equity is access to internet-enabled devices at home such as a desktop, laptop, or tablet computer. Low-income households were about twice as likely as those with higher incomes to report that they had an inadequate number of computers or other digital devices to access the internet at home (24 percent vs. 13 percent).

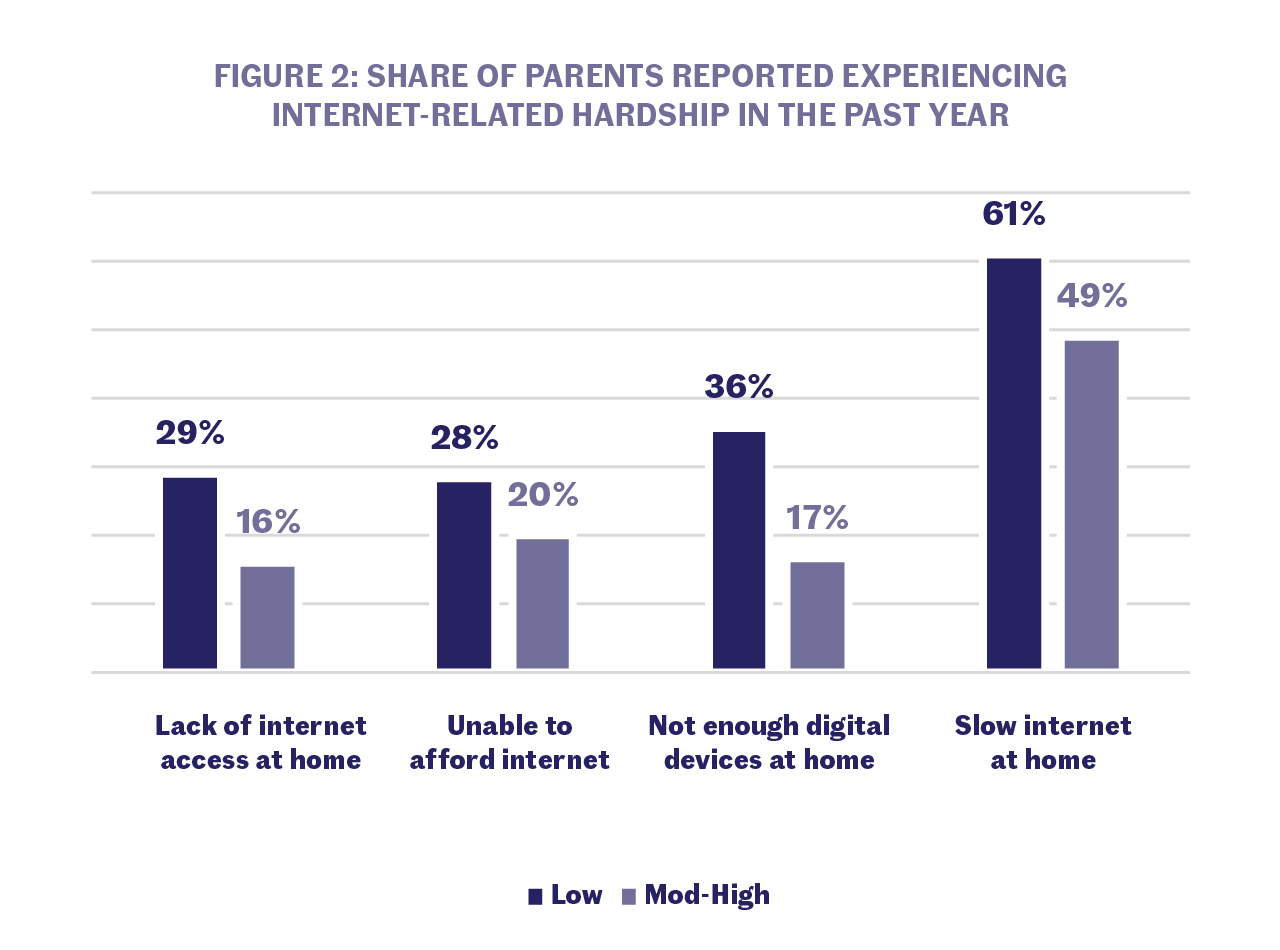

There were particularly troubling disparities in internet access among families with children. About three out of every ten low-income parents said that they struggled to afford internet access in the past year, nearly double the share of moderate to higher income parents who did.

More than a third of low-income parents said that their household lacked enough computers or other digital devices at home, twice the share of parents with moderate to higher incomes.

A slow internet connection was also a challenge across incomes, but low-income parents are more likely than their higher income counterparts to experience this issue: six out of every ten reported experiencing this problem, in contrast to just under half of those with moderate to higher incomes.

The digital divide is most pronounced among low-income New Yorkers of color, Bronx residents, those without a college education, and public housing residents

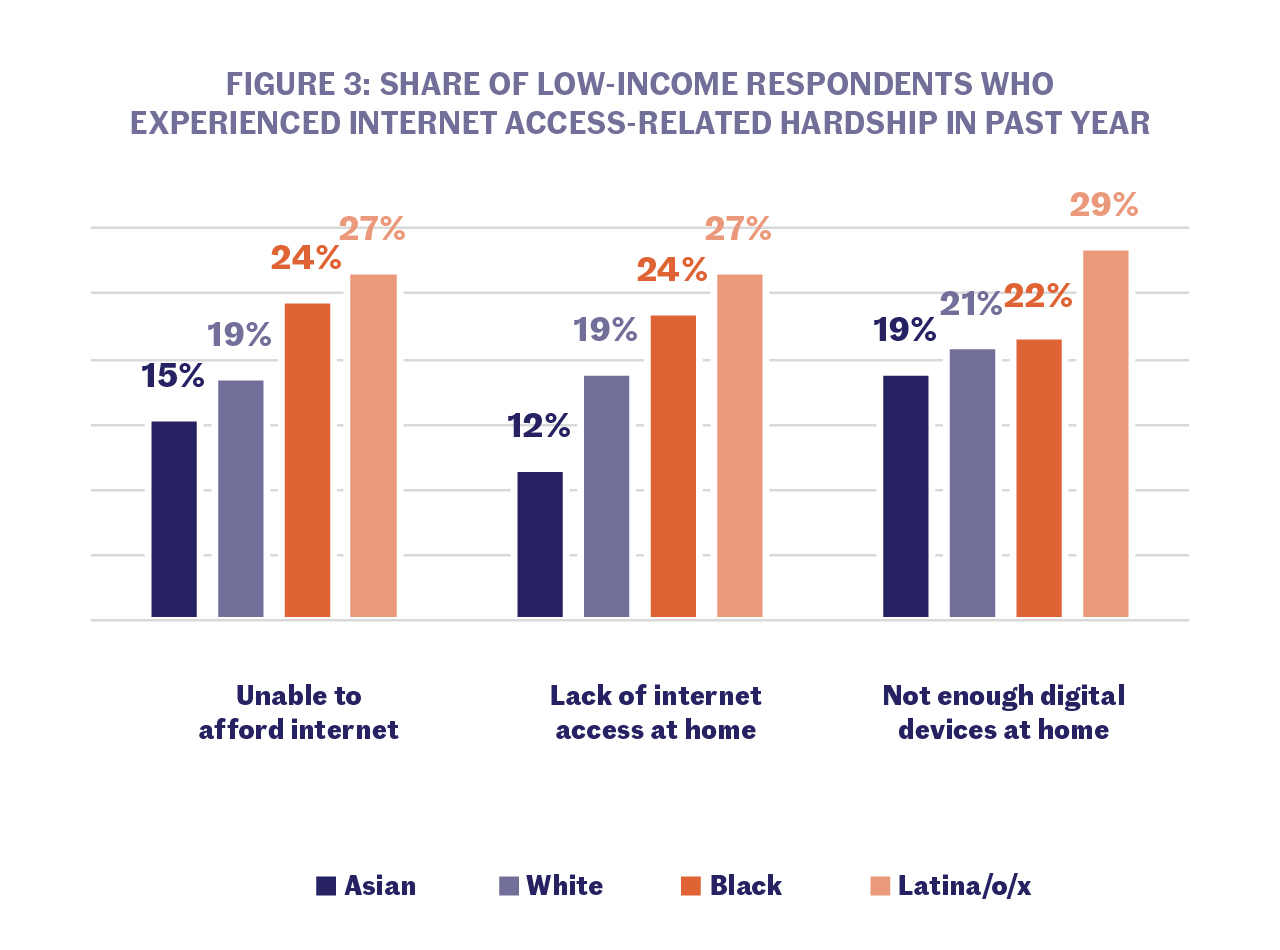

Among low-income respondents, Black and Latina/o/x New Yorkers were most likely to report that they lacked home internet access, had difficulties with affording the cost of internet service in the past year, and had too few digital devices at home. Nearly three out of every ten low-income Latina/o/x New Yorkers had an inadequate number of internet-enabled devices in their household, compared to 19 percent of White New Yorkers. Among low-income respondents, Latina/o/x New Yorkers were twice as likely as White New Yorkers to lack home internet access.

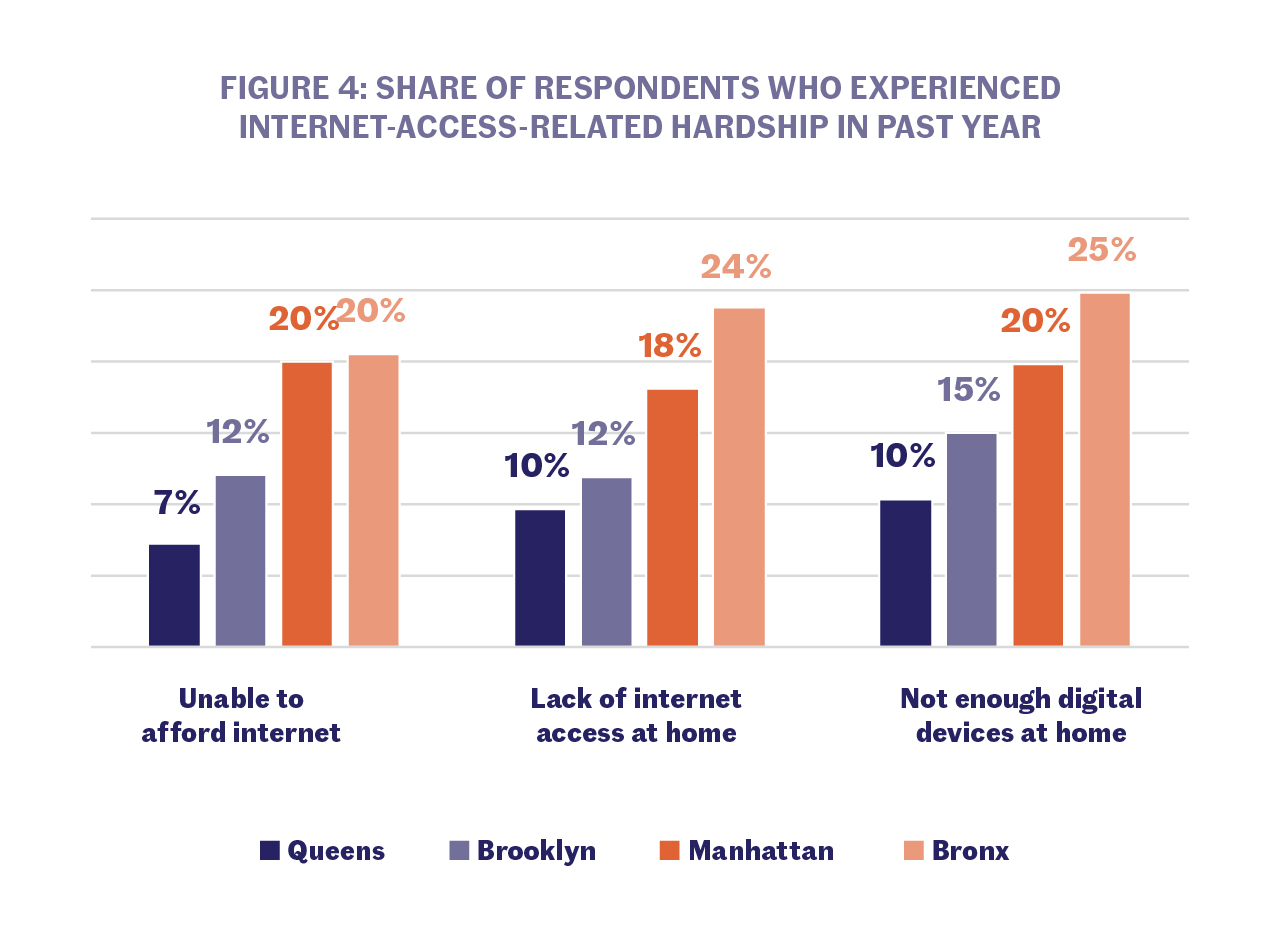

Households in the Bronx were most likely to report difficulties with accessing the internet at home. Nearly a quarter of Bronx respondents reported that their household lacked home internet access in the past year, double the share of Brooklyn and Queens respondents who lacked home internet access. One out of every four Bronx residents said that they had an inadequate number of computers or other digital devices at home, more than twice the share of Queens residents.

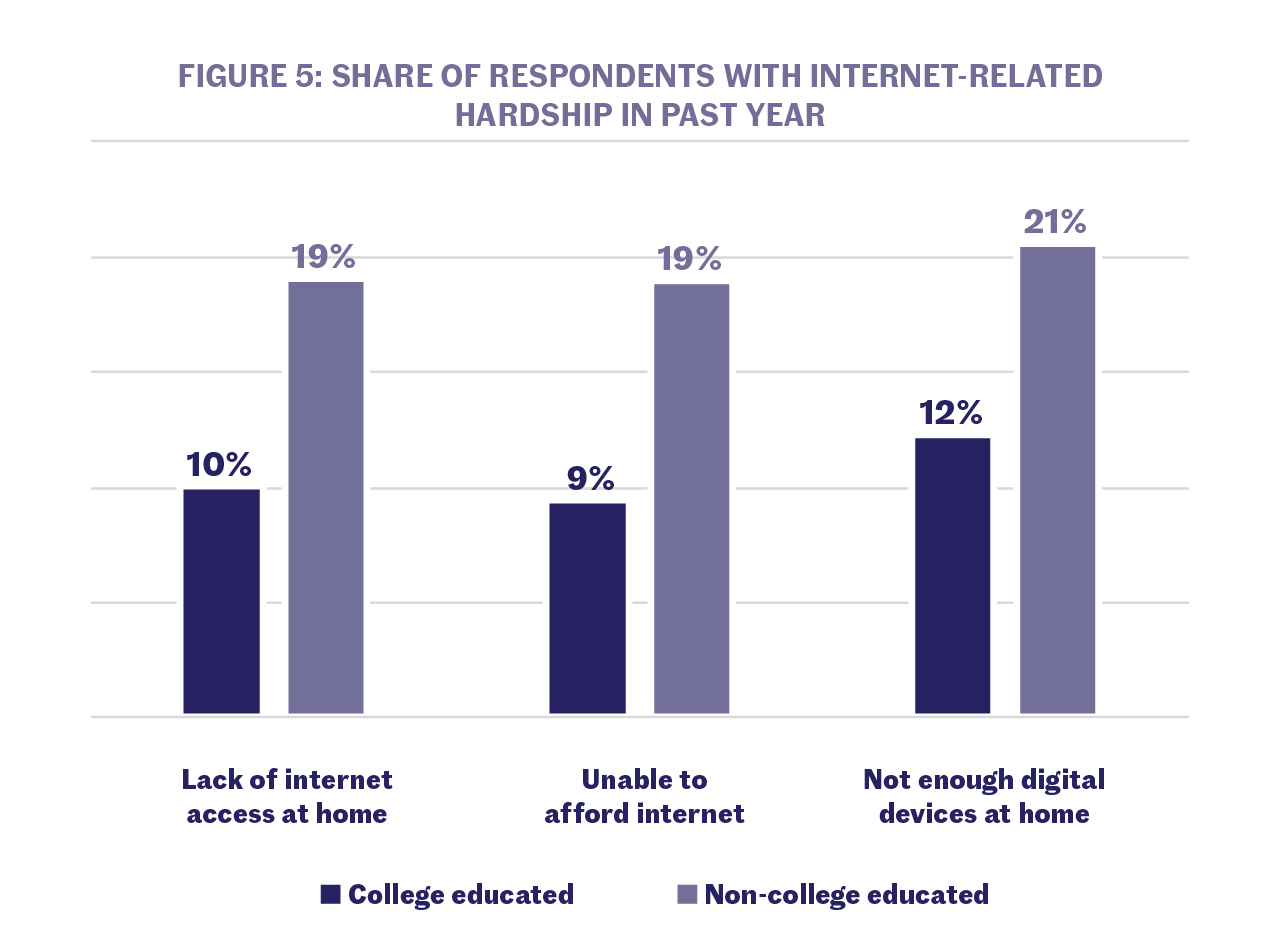

Respondents without a four-year college degree were twice as likely as those with a college education to report lacking internet access at home or to struggle with the cost of internet access (Figure 5). The digital divide by educational attainment is concerning given that access to affordable, reliable high-speed internet is more important than ever for upward mobility and taking full advantage of opportunities in education and employment.

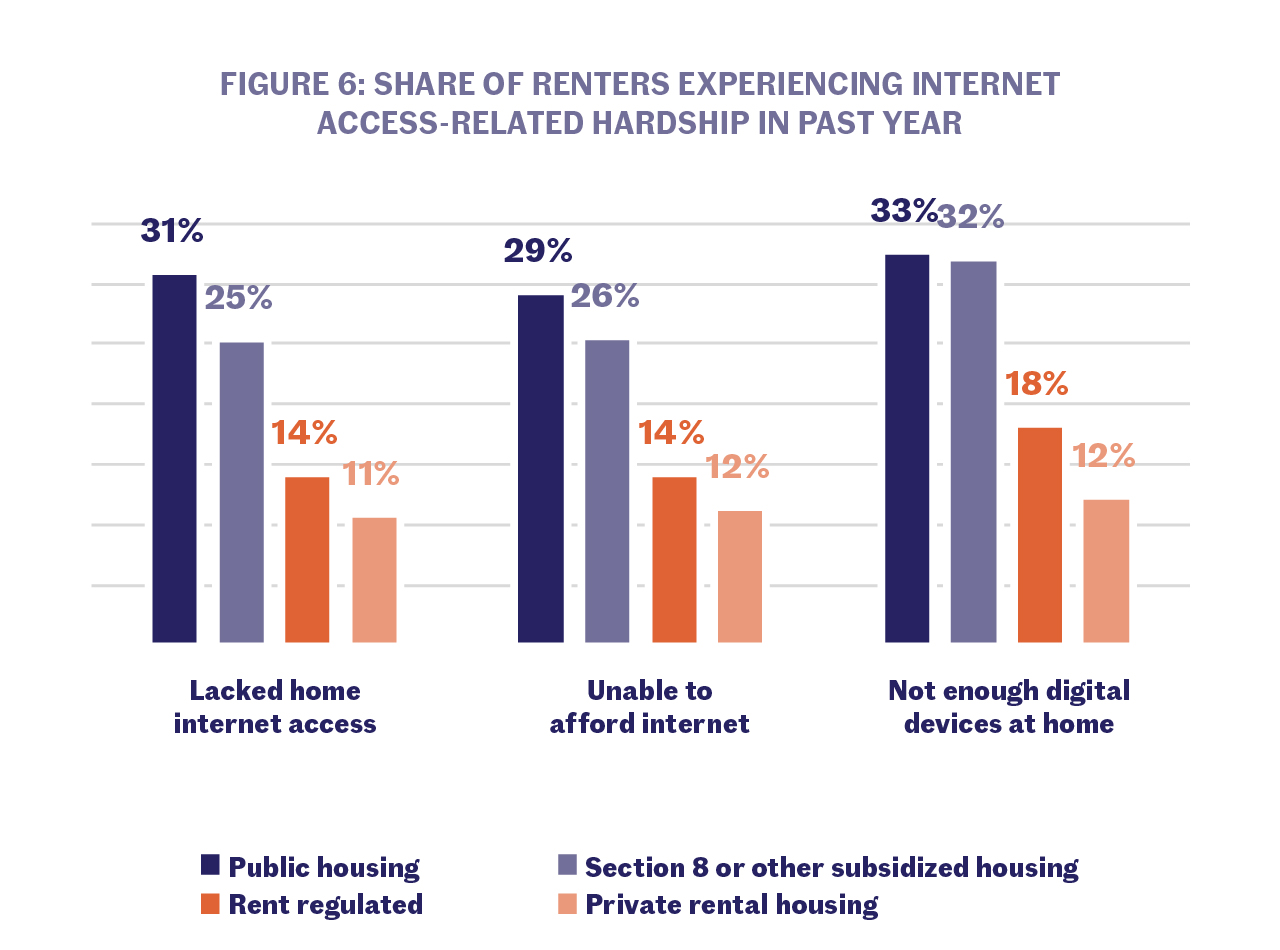

Last July, former Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that the city would “accelerate” its plan to roll out affordable high-speed internet access for people in public housing and low-income neighborhoods hit hardest by the pandemic. Our 2021 Unheard Third data shows that digital equity remains an issue for many public housing residents and those in other subsidized housing. A third of public housing residents and a similar share of those with Section 8 vouchers or those living in other subsidized housing units reported that they had an inadequate number of digital devices to access the internet at home, nearly triple the share of those in private market rentals. Thirty-one percent of public housing residents said that they lacked home internet access, about three times higher than the share of renters living in private market units. Additionally, 29 percent of public housing residents reported difficulty with affording the cost of internet access, more than double the share of those in private market rentals. Unfortunately for New Yorkers, the current mayoral administration has decided to put a pause on plans to pursue municipal broadband.

The digital divide is especially disruptive for low-income New Yorkers seeking socio-economic, health and education services and opportunities.

The digital divide is preventing New Yorkers from climbing up the economic ladder. An inadequate number of digital devices in the household and a slow internet connection are keeping sizable shares of New Yorkers from completing important tasks related to their health, education, and job-related training. Four out of every ten low-income New Yorkers with problems related to internet access reported that these issues kept them from completing online school, and nearly a third said that they were a barrier to completing online job-related training (Figure 7). Public housing residents were especially likely to experience challenges with completing these important tasks, with nearly half reporting that difficulties with internet access kept them from completing online education or job training, as well as attending telehealth visits.

More troubling, compared to 44 percent of moderate-to-higher-income parents, a much higher share (58 percent) of low-income parents said that an inadequate number of digital devices in the household and a slow internet connection kept them or a member of their household from participating in online school or completing their online schoolwork. This has broad implications for low-income children in our city’s public schools, who have struggled with remote learning due to lack of internet devices and internet access throughout the pandemic.

Across incomes, parents in NYC are deeply concerned about their children’s education prospects due to the pandemic.

Nearly two-thirds (65 percent) of low-income parents surveyed said that the impacts from the pandemic will likely result in a long-lasting setback for their children’s education, compared to 56 percent of moderate to higher income parents. Among low-income parents, a staggering 74 percent of Latina/o/x parents said that the impacts from the pandemic will likely result in a long-lasting setback for their children’s education.

Conclusion and recommendations

In January 2020, Mayor Bill de Blasio released an Internet Master Plan to expand equitable access to broadband internet, with the goal of making broadband universal for all New Yorkers. The Internet Master Plan correctly identifies the inability of private market solutions to solve the digital divide in New York City, but it also relies on granting city assets to the private sector to broaden accessibility and lower internet service costs. We contend that so long as internet access comes at a cost, there will always be New Yorkers who lack adequate access to the internet.

New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications (DoITT) recognizes that “access to high-speed and affordable internet service is no longer a luxury, but a requirement for New Yorkers to function adequately in the modern world.”[9] We agree. Given what we know about the necessity of internet access and the prevalence of technology in modern life, a path towards free municipal broadband is in the best interests of all New Yorkers.

Municipal broadband could mean that high-speed internet is treated as a public good, just like schools, streetlights, roads, bridges, and parks. Under this model, municipalities build and own the infrastructure for providing internet service throughout the municipality. This means that all residents would gain access to the internet without payment. Furthermore, research has shown that municipal broadband can outperform private sector internet service providers in terms of both affordability and speed.[10]

Unfortunately for New Yorkers, the current mayoral administration has decided to put a pause on plans to pursue municipal broadband for reasons that remain unclear, despite the current mayor supporting the Internet Master Plan initiative in the past.[11] While the current administration considers whether or not to pursue any path toward municipal broadband, here are our recommendations for taking immediate steps toward closing the digital divide through an equity-focused lens:

- Pilot municipal broadband in the Bronx: New York City should pilot municipal broadband projects in the Bronx, where the digital divide is most pronounced. Starting with areas that experience the highest access needs would directly challenge the inequities we have found in internet access. While Mayor Adams has recently begun installing free internet kiosks in the Bronx, these kiosks are not a replacement for having high-speed internet in one’s home or while on the go.[12] The city should engage in a participatory process with Bronx residents to ensure that internet service provision is aligned with community needs.

- Provide NYCHA residents with free internet access: Though internet service providers work with NYCHA to provide residents with affordable internet in some developments (and free service in some cases), our findings suggest that this provision is not enough to offset the needs of NYCHA residents.[13] Nearly half of respondents in public housing had difficulties accessing telehealth, job training, and online schooling. This lack of access to essential services and opportunities works toward perpetuating poverty rather than ending it. A free, high-speed internet program in NYCHA, at-large, would work towards narrowing the digital divide in New York City and by doing so, removing barriers to economic and education opportunities.

- Ensure public school students have high-speed internet access and working devices: There was an effort to provide devices at the height of the pandemic, but it is unclear how much of that demand was met, especially for families who speak languages other than English.[14] Though the DOE has moved toward in-person instruction, students at the February 16, 2022 Panel for Education Policy meeting made impassioned arguments for remote learning to continue.[15] They are afraid not just for themselves but others that they may infect others in their homes and during their commutes if they contract COVID-19. NYC should make sure that when students study from home, they have the tools to do so and the public needs access to have an accurate measurement of how close the NYCDOE is to meeting the need of its students.

- Study the feasibility of municipal broadband throughout the state: Former Governor Cuomo rejected a bill that called for the study of municipal broadband and its feasibility within the state.[16] The current legislature should reconsider this bill now that the state has new leadership. State resources would be instrumental in improving internet accessibility in New York City and across the state.

Survey Methodology

The Community Service Society of New York designed this survey in collaboration with Lake Research Partners, who administered the survey by phone using professional interviewers. The survey was conducted from July 8th through August 10th, 2021. The survey reached a total of 1,763 New York City residents, age 18 or older, divided into two samples. 1,110 low-income residents (up to 200% of federal poverty standards, or FPL) comprise the first sample including 533 poor respondents, from HH earning at or below 100% FPL (69.4% conducted by cell phone) and 577 near-poor respondents, from HH earning 101% - 200% FPL (71.1% conducted by cell phone). 653 moderate- and higher- income residents (above 200% FPL) comprise the second sample, including 389 moderate-income respondents, from HH earning 201% - 400% FPL (70.2% conducted by cell phone) and 264 higher-income respondents, from HH earning above 400% FPL (61.7% conducted by cell phone).

Landline telephone numbers for the low-income sample were drawn using random digit dial (RDD) among exchanges in census tracts with an average annual income of no more than $44,660. Telephone numbers for the higher-income sample were drawn using RDD in exchanges in the remaining census tracts. The data were weighted slightly by income level, gender, region, age, immigrant status, and race in order to ensure that it accurately reflects the demographic configuration of these populations. Interviews were conducted in English (1,662), Spanish (83), and Chinese (18). The low-income sample was weighted down into the total to make an effective sample of 600 New Yorkers.

In interpreting survey results, all sample surveys are subject to possible sampling error; that is, the results of a survey may differ from those which would be obtained if the entire population were interviewed. The size of the sampling error depends on both the total number of respondents in the survey and the percentage distribution of responses to a particular question. The margin of error for the entire survey is +/- 2.3%, for the low-income component is +/- 2.9%, and for the higher-income component is +/- 3.8%, all at the 95% confidence interval.

For questions related to the survey, please reach out to Emerita Torres, Vice President of Policy Research and Advocacy, at etorres@cssny.org.

Notes

1. Irving, L. (2017, October 30). The Digital Divide: Twenty years later. HuffPost. Retrieved August 24, 2022, from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-origin-and-evolution-of-the-digital-divide_n_59cd109ae4b0e005cc5725c5

2. Vogels, E. A. (2021). Digital divide persists even as Americans with lower incomes make gains in technology adoption. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/06/22/digital-divide-persists-even-as-americans-with-lower-incomes-make-gains-in-tech-adoption/

3. US Census Bureau, 2019 1-year American Community Survey estimates. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=broadband&g=0400000US36_1600000US3651000

4. US Census Bureau, 2019 1-year American Community Survey estimates. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=broadband&g=0400000US36_1600000US3651000

5. Amin, Reema. July 29, 2020. The education department distributed 321K iPads to NYC students for remote learning. Now principals have to get them back. ny.chalkbeat.org/2020/7/29/21347043/remote-learning-devices-distribution-nyc

6. NYCDOE InfoHub, 2020-21 Device Request Data. infohub.nyced.org/reports/government-reports/remote-learning-report

7. NY Const art XI § 1

8. Legal Services NYC, Arnold & Peter, and the Education Law Center are representing several families who are suing state and city officials for failing to adequately address needs of low-income students during the pandemic. Read about the case, here: https://www.arnoldporter.com/en/perspectives/news/2022/01/remote-learning-lawsuit

9. New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | Initiatives | Broadband. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doitt/initiatives/broadband.page

10. Johnston, Ryan. July 22, 2019. Municipally run internet tops national speed test rankings. https://statescoop.com/municipal-Internet-isps-pcmagazine-speed-test-study/

11. Jaclyn Jeffrey-Wilensky. (n.d.). NYC's plan for public internet paused under mayor Adams. Gothamist. Retrieved August 24, 2022, from https://gothamist.com/news/nycs-plan-for-public-internet-paused-under-mayor-adams

12. Gartland, M. (2022, July 9). NYC set to install hundreds of new high-speed internet kiosks to bridge digital divide. New York Daily News. Retrieved August 24, 2022, from https://www.nydailynews.com/news/politics/new-york-elections-government/ny-adams-fraser-linknyc-kiosks-digital-divide-20220709-6unptmsbdrhhpdokusrpnuzjsa-story.html

13. Garber, N. (2022, April 28). UES NYCHA Residents Get Free Broadband Internet through new program. Upper East Side, NY Patch. Retrieved August 24, 2022, from https://patch.com/new-york/upper-east-side-nyc/ues-nycha-residents-get-free-broadband-internet-through-new-program

14. Testimony from parents at the February 28th City Council hearing on English Language Learners suggested that the NYCDOE was unable to reach

15. Panel for Education Policy Meeting. February 16, 2022. https://learndoe.org/pep/archive-pep-feb16-2022/

16. A02037/S06041-A directs the department of public service to study feasibility of a municipal broadband program with the state. https://nyassembly.gov/leg/?default_fld=&leg_video=&bn=A02037&term=2019&Summary=Y&Actions=Y&Memo=Y&Text=Y