A sudden shock to an overburdened system: NYC housing & COVID-19

Oksana MironovaThomas J. Waters

We dedicate this piece to the memory of our friend and colleague Tom Waters, who passed away on April 4th. Tom was a sharp analyst and a respected affordable housing advocate. This was the last piece he worked on for CSS, advocating for a dignified and comprehensive housing response to the pandemic. His analytical and nuanced voice will be missed. You can find more of his research and publications here.

COVID-19 intensified the city’s ongoing housing crisis, already a daily reality for four in ten low-income New Yorkers who are homeless or severely rent burdened. The pandemic is now bringing hundreds of thousands of others to the brink. In recent years, the New York housing justice movement has achieved major legislative victories, including the right to counsel law and a generational strengthening and expansion of rent regulation. These successes provide tenants with tools to cope with what will be long-term economic impacts of the pandemic, and an organizational framework to influence the political decision-making process in Albany. With the housing system under a major and unexpected stressor, there is an immediate need for an infusion of public funding for housing permanently affordable to low-income people, and a broader reorientation of the public sector’s role in housing provision and stewardship.

Pre-pandemic housing landscape

Before March 2020, many low-income New Yorkers were already living on the edge, with rent eating up a substantial portion of their earnings. Our previous research has shown that among low-income rent stabilized households, the median rent to income ratio—the share of income a household spends on rent—increased from 40 percent in 2002 to 52 percent in 2017.

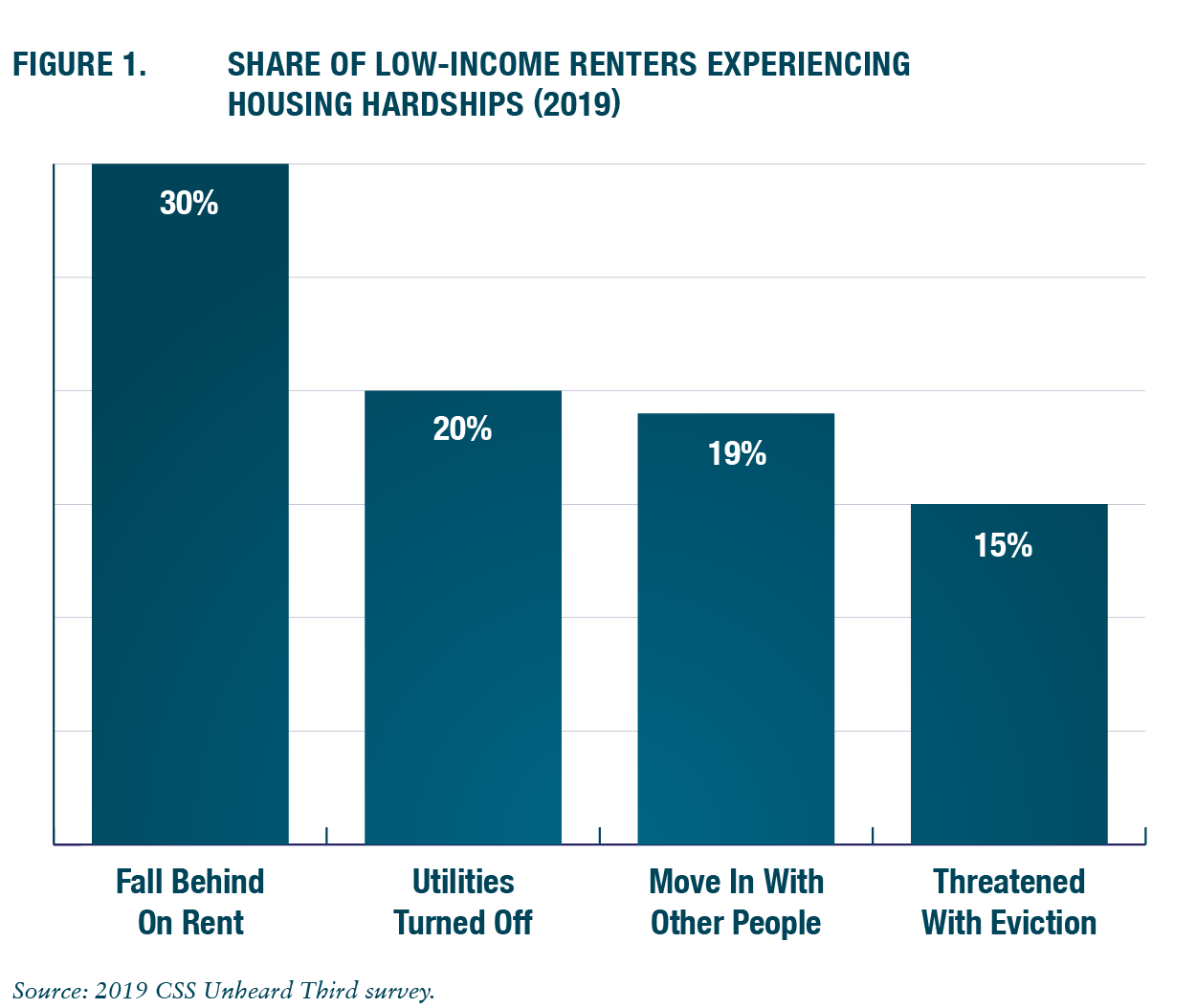

After decades of climbing housing costs, low-income New York City renters were experiencing high rates of housing hardships. In 2019, 30 percent fell behind on rent, 20 percent had utilities shut off, 19 percent had to move in with other people, and 15 percent were threatened with an eviction. The vast majority of low-income renters–70 percent–had less than $1000 in savings for an emergency, like an unexpected loss of income or a hospitalization.

The pandemic exacerbates a long brewing crisis

The sudden onset of the pandemic not only created an impossible situation for New Yorkers who were already homeless and housing-insecure, but is now bringing many others closer to the edge. The city has 312,000 renter households who are in the labor force, do not receive federal housing assistance, and earn incomes below twice the poverty level.1 According to research done by the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy, 34 percent of New Yorkers earning under $50K reported that they or someone in their household has lost their job as a result of pandemic in the second and third week of March [Note: the CUNY survey was conducted before harsher social distancing measures went into effect, meaning that the job loss rate by now is much higher]. And, 70 percent of low-income New Yorkers have less than $1K in savings for an emergency. Putting that together, at least 74,000 low-income households (about 156,000 people) will find it hard or impossible to make their April rent, as of March 22. Given the city’s high rents and the long reaching impact of the economic downturn, an additional 52,000 moderate-income households (about 109,000 people) may also be impacted.2 Recently expanded unemployment insurance—covering more workers, with higher weekly benefits–will help some, but will only partially replace wages and leave out important segments of the New York City workforce, like undocumented workers. The stimulus check will offer some reprieve as well, but it is a one-time payment that also excludes undocumented New Yorkers.

Without additional action by the state, accumulating rent arrears will propel hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers into debt and years of housing insecurity. It will also threaten the ability of nonprofit and mission-based landlords to operate their housing.

Pandemic housing assistance: What’s already enacted?

With significant pressure from grassroots and nonprofit organizations, the local and federal governments have taken some steps to mitigate the immediate impacts of the pandemic on housing. There is a 90-day eviction moratorium in place statewide, one of the most holistic measures in the U.S. The New York City Human Resources Administration (HRA) has emergency cash assistance grants available for people who have lost income as a result of the pandemic and are unable to pay rent, among other resources (see CSS’s Benefits Plus guide).

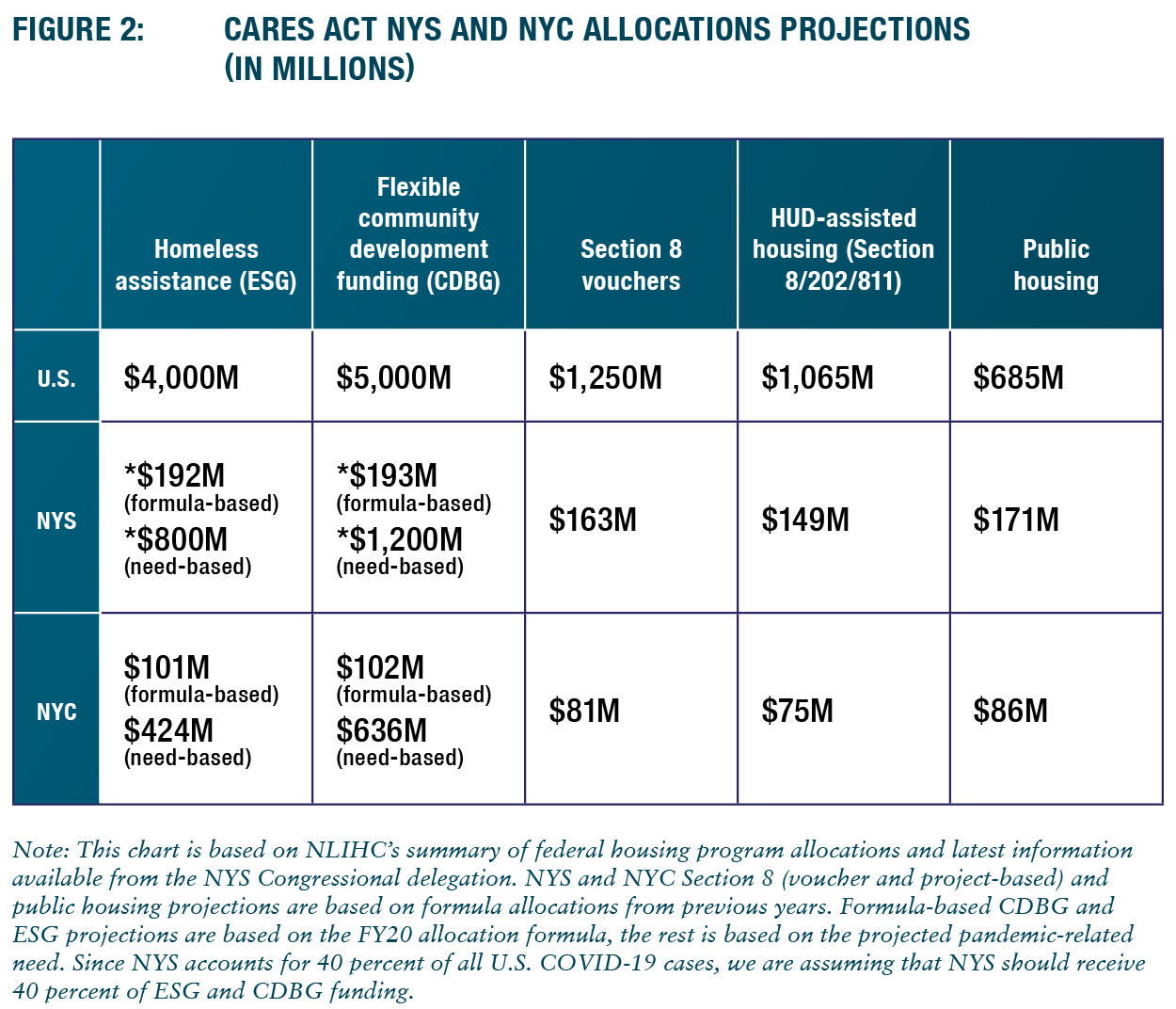

On the federal level, housing provisions within the stimulus package (the CARES Act) largely focus on households already receiving federal housing assistance, including Section 8 voucher holders and residents of public and subsidized housing. In recent years, New York State received $2.7B toward Section 8 vouchers, $1.6B toward public housing, and $1.6B toward HUD-assisted housing contracts. Assuming similar distribution levels (see Figure 2 below), the additional $163M toward vouchers, $171M toward public housing, and $149M toward HUD-assisted housing will help cover rents of those residents who lost all or much of their income, and help public housing agencies and private landlords respond to the pandemic. It is unclear if this funding will cover all the immediate pandemic-related costs. It is certainly insufficient for the long-term recovery needs of public housing authorities, like the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA).

Supplementing the 90-day NYS eviction moratorium, the CARES Act places a 120-day moratorium on all evictions in federally-assisted housing, including buildings funded by Low Income Housing Tax Credits and federally-backed mortgage loans.

Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) and Emergency Solutions Grants (ESG) are more flexible, and can help people who do not live in federally-assisted housing. ESG funds can be used for eviction prevention, short-term rental assistance, homeless services, and rapid rehousing. CDBG funds can be used for rental assistance, housing development and rehabilitation, and public services. In the first 30 days, New York State will receive $192M in ESG funding and $193M in CDBG funding from the federal government, based on the 2020 allocation formula. The remainder will be distributed based on the scale of local need. As of March, NYS accounted for 40 percent of the COVID-19 cases in the U.S., which could mean that it would potentially qualify for up to $800M and $1.2B of ESG and CDBG funding, respectively. This projection is likely overly optimistic, since to date the federal government has failed to recognize the magnitude of New York State’s need.

In addition to direct housing assistance, the stimulus package includes other funding mechanisms that can be used toward housing costs, like the Coronavirus Relief Fund ($150B) and the FEMA Disaster Relief Fund ($45B). For example, if requested from state and local governments, FEMA funding can be used for short-term shelter development.

Pandemic housing assistance: What else is needed (short term)?

While the eviction moratorium and expanded resources for HUD-assisted households are important first steps, all levels of government need to take additional decisive action immediately. New York State should use all modes of federal assistance–including CDBG, ESG, and disaster funds–to immediately address the ballooning crisis among unsheltered New Yorkers as outlined in this call from homelessness groups: enforcing safety measures in shelters, ending sweeps and other types of targeting of homeless New Yorkers, and using vacant hotels, public, and private apartments for emergency housing. Other cities, like New Orleans and Los Angeles are implementing such measures.

At the same time, the New York congressional delegation should fight for $11.5B more in homelessness program funding in the fourth stimulus package. We can expect that all federal funding will continue to punitively exclude undocumented and mixed-status households from recovery assistance. New York, as a proclaimed sanctuary state, needs to mitigate this by extending state and local housing assistance to undocumented households.

New York’s rent laws create a framework for emergency intervention in the rental market. Tenant advocates recently called for a suspension of the Rent Guidelines Board (RGB) hearings for 2020, and a rent freeze for the city’s one million regulated units. At least two members of the RGB, and Mayor de Blasio, have since showed support for this plan.

Rent regulation covers about half of the city’s rental housing stock, meaning that 217,000 low-income renter households living in unregulated housing will not benefit from the RGB rent freeze. And, there are early signs that landlords of unregulated buildings are using the pandemic to justify significant rent hikes. The state should take emergency action to guarantee automatic renewal of leases for all tenants at the current rent levels for the duration of the crisis.

While beneficial for residents who have held on to their jobs, a rent freeze will not be sufficient for 126,000 low- and moderate-income households who have lost much or all of their income as of March 22nd and do not have emergency savings to fall back on. Without coordinated action, New York is set to face a flood of evictions for non-payment of rent whenever the eviction moratorium is lifted. This, in turn, will overwhelm the nonprofit and public social safety net systems, which were already overburdened, and are now facing their own pandemic-related underfunding crises.

There are two bills in the state legislature that address this fast moving issue: one, introduced by Senator Gianaris–and broadly supported by grassroots housing justice organizations–suspends rent payments for 90 days for renters and small businesses impacted by the pandemic. The other, introduced by Senator Kavanagh, establishes an emergency rental assistance program for rent-burdened tenants impacted by the pandemic. For legislation to successfully meet the dire needs of New Yorkers unable to make the rent this spring, it needs to be strong enough to withstand legal challenges from landlords in the coming months, prescriptive about mechanisms for establishing need, clear about who is included and who is excluded, and include a strong oversight mechanism. Concurrently, on the federal level, the forth stimulus package needs to include a significant allocation, at least $100B, toward emergency rental assistance, to ensure that nonprofit and mission-driven landlords are able to continue operating through the economic recession that will follow the pandemic.

Rebuilding After the Pandemic

COVID-19 is the latest stressor that exposes a rolling, structural crisis in our housing provision system. Before the pandemic, even in a strong economy, four in ten low-income New Yorkers were either homeless or paying more than half of their income in rent, a result of decades of cutbacks to our social safety net. Without a major re-definition of the public sector’s role in housing provision and stewardship, these often-cited statistics will only become grimmer. Before the pandemic, advocacy toward such a vision was beginning to gain ground. Local and national groups were coalescing around transformative housing visions like the Homes Guarantee proposal and the Green New Deal for public housing. Democratic candidates were proposing billions of dollars in federal funding toward public housing repair, making Section 8 vouchers an entitlement, addressing racial discrimination in housing, and innovative housing models like community land trusts. As the immediate response to the pandemic extends into what is likely to be a multi-year recovery, we need bold housing proposals, like a major commitment to public and social housing in any large-scale federal relief infrastructure project.

1. This calculation excludes Section 8 voucher holders, as well as public housing and project-based Section 8 residents, because their rents will be adjusted to compensate for income loss; Low income residents earn under 200 percent of the federal poverty line or $41,000 for a family of three.

2. We will update this calculation once additional job loss numbers are available. Moderate income households earn under 400 percent of the federal poverty line or about $82,000 for a family of three.